“We will attack!” Prince Eugene at Peterwardein

Originally published in Military Heritage Magazine

by Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

Thousands of dead Turkish soldiers choked the river and littered its bank. It was the fall of 1697 and the young Imperial Field Marshall, Prince Eugene of Savoy, had just vanquished the Ottoman army at Zenta (or Senta), on Hungary’s River Tiza. His decisive victory brought about the 1699 Peace of Karlowitz and the end of the Second Turkish War (1683-1699) that had pitted the Holy Alliance of Poland, Venice, Russia, and Austria’s Holy Roman Empire against the Ottoman Turks. With the exception of the Ottoman Banat (a border march) of Temesvár, the treaty left Austria in possession of all of Hungary and Transylvania.1

Eugene became a European hero and Austria a major European power. Peace had scarcely been secured in the east, however, when the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) broke out in the west. It pitted the Grand Alliance of England, the Netherlands, and the Empire against the French and Spanish. Together with his friend, the brilliant general Duke of Marlborough, Eugene won several great victories for the allies.2

In the east, however, the smoldering Turkish Empire was not yet finished, not by a long shot. Like their foes, the Ottomans regarded the Karlowitz treaty as little more than an armistice. The Ottoman Empire of Sultan Ahmed Khan III Najib (r. 1703 and 1730) still spanned over two million square kilometers. With such a vast territory and burgeoning population, it was only a matter of time before the Ottomans would recuperate their manpower losses. In 1710 that time came. Infuriated by Russian border violations and new fortifications in the Ukraine, the Porte (Ottoman High Command) declared war on Russia.3

Submitting to the Ottomans after a lengthy standoff at River Pruth

A year later, an outmaneuvered Russian army submitted to the Ottomans after a lengthy standoff on the River Pruth. Humiliated, Peter the Great accepted an unfavorable peace treaty that returned Azov and other fortresses to the Ottomans. With the Russians cowed, the Ottomans used a Venetian-inspired uprising in Montenegro as an excuse to resume their war with Venice in 1714. Grand Vizier Damad (also known as Silahdar) Ali-Pasha, the Sultan’s son-in-law and personal favorite, led the Turks in an assault on the Venetian Kingdom of the Morea (the Greek Peloponnese). The Ottomans were not so foolish, however, so as not to realize that their victories in Russia and in the Morea unnerved their old archenemy, Austria.4

Wishing for the moon

Vienna basked in the summer heat of 1715 when, in a pompous ceremony, Ibrahim, the sultan’s müteferrika (a member of the Ottoman palace ‘elite’) walked up to a seated, short and wiry individual who was surrounded by the chief Imperial officers of state. This was Eugene, now in his fifties and president of the Hofkriegsrat (the Imperial War Council). Though a plain brown tunic was his more usual attire, in light of the occasion Eugene now wore gold-embroidered red silk.

From under his broad brimmed hat, Prince Eugene eyed the Turkish representative. The müteferrika presented a letter from the Grand Vizier Damad by which Damad expressed his hope for the emperor’s neutrality in the Ottoman war with Venice. It was a not to be. Damad might as well have wished for the moon.5

Eugene fully realized that no matter how cordial the Turks presented themselves, it was only a matter of time before the Ottoman behemoth swung towards the empire. Urged on by Eugene, in April 1716 Emperor Charles VI of the Imperial House of Habsburg renewed Austria’s old alliance with Venice. Consequently, Charles VI insisted that the Ottomans adhere to the treaty of Karlowitz and return to Venice all the lands they had taken.6

A new declaration of war

On May 15, 1716, the Porte answered Austria’s demands with a declaration of war. The Morea had already fallen to Grand Vizier Damad Ali-Pasha in the late summer of the previous year and the Venetians were hard pressed to hold onto Albania and the Dalmatian coast. The Porte was free to direct the brunt of its martial might against Austria. Leading it would be the Damad Ali-Pasha.7

At Modon in the Morea, Damad had paid a reward for every Christian brought to his tent so he could personally relish the sight of their decapitations. He also executed any Turks who had been foolish enough to embrace Christianity while under Venetian rule. Now he wrote to Eugene, “there is no doubt that the blood which is going to flow on both sides will fall like a curse upon you, your children and your children’s children until the last judgement.” Damad inspired his own commanders with the words, “attack the infidels without mercy … Be neither elated nor down-hearted, and you will triumph.”8

By fluke more than by design

For the first time since Suleiman the Magnificent (1490-1566), war in the Balkans was forced upon the Ottomans instead of the other way around. This suited Eugene just fine because, by fluke more than by design, European power politics following the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714 resulted in an unusual period of peace in the west.9

The chief catalysts for this peace were the 1715 death of Austria’s old European enemy, France’s Louis XIV, and the resurgence of the Whig party in England in 1714. Louis XIV was succeeded by his great grandson Louis XV. In the event of the child King’s death, his regent, the Duke of Orleans, was more worried about safeguarding his own claim to the throne from his rival claimant, Philip V of Spain, than in starting new wars. England’s Whigs meanwhile were too occupied with the Jacobite opposition and the danger of rebellions to get involved in Continental struggles.10

This left the threat of Philip V who resented Emperor Charles VI’s claim of Naples, Sardinia, Milan and the Spanish Netherlands, ceded to him as a result of the Spanish Succession War. To counter Spain, Austria allied herself with England. Eugene and Gundaker von Starhemberg, the President of the Ministerial Bank Deputation, hoped that the alliance would provide “security during the Turkish War.” Pope Clement XI, who heralded the war against the Turks as a crusade, obtained further peace of mind. He promised to do all he could to protect Charles’ Italian lands and gained Philip’s word that he would not move against the emperor if the latter went to war with the Turks. Unfortunately, there were others at the Imperial court that saw the English alliance as an opportunity to renew the conflict with Spain. To Eugene’s delight, such plans were scrapped when the English withheld the aid of their navy (the Imperials had none of their own!).11

Austria to bear the brunt of the war

Thus, Eugene was free to concentrate on the Turks in the east, which is what he really wanted to do. Moreover, Pope Clement XI offered 500,000 florins from church lands for the effort. Nonetheless, the brunt of the war costs would fall on Austria. Indeed, unlike the previous two Turkish Wars, this one was to be virtually an almost exclusively Austrian war. The Venetians were busy defending the Ionian Islands, and of the German princes, only Max Emmanuel of Bavaria sent a sizeable contingent of troops.

Since the Austrian war commissariat already owned 23 million gulden in pensions and back pay, the whole financial system had to be reorganized according to Eugene’s and Starhemberg’s wishes. A further loan of two million gulden was obtained from the United Provinces.12

Already by September 1715, before the Porte’s actual declaration of war, troops were moved into Hungary. The collection of an army had commenced and made substantial progress even before the Porte’s declaration of war. Difficulties in the form of droughts and floods intervened and Eugene himself remained in Vienna until July 2, 1716, to make sure of sufficient supplies and funds, but his diligence paid off. After a ride of seven days he reached the village of Futak (Futog) on the northern bank of Danube and west of the fortress town of Peterwardein (Petrovaradin), the “Gibraltar of Hungary.” There he beheld his army of 65,000 men, which he described to be “in a very fine serviceable condition.” His comments were in stark contrast to those he made in 1697 when he had been given command of an Imperial army in which there “are many diseases but only a little money.”13

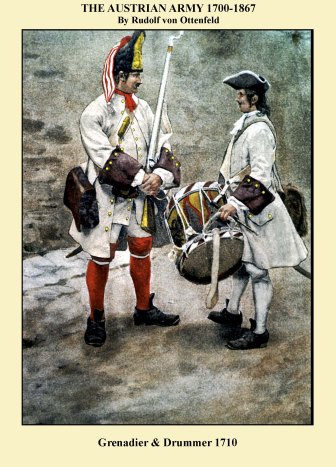

Hardy peasant louts, vagabonds and nobles

Through their thick walrus mustaches, Prince Eugene’s troopers no doubt cursed and muttered over the usual hardships of war. Theirs was a hard life. They fought not for cause and country but for money. Though hardy peasant louts were the favorite source of recruits for the Imperial Army, most of the soldiers—like those of all 18th-century armies—were from the bottom of society: vagabonds, criminals and beggars, especially in the infantry. Productive tradesmen and farmers were usually exempt from military service because they kept the economy healthy. Only through strict, at times excessively brutal, discipline were recruits welded into formidable fighting machines. Nevertheless, Eugene’s soldiers, flushed with recent victories in the Rhineland and with unabated confidence in a leader who genuinely cared for their well being, were ready for a fight.14

Eugene’s officers hailed from a stratum of society completely opposite to that of their men, yet one which- like that of their men- was generally unproductive: the nobility. Eugene’s had personally chosen most of his senior officers. Commanding the infantry were the bold Field Marshal Prince Alexander von Württemberg and the eccentric Field Marshal Sigbert Heister. Eugene personally disliked Heister whose extreme brutality with Hungarian rebels in the past had backfired for the Imperials and caused Heister to be hated, and feared, all over Hungary. However, on the flip side, there was no denying his personal daring, bravery and unrelenting tenacity.15

Leading the cavalry were Field Marshal Count Johann von Pálffy, whom Eugene considered an able if not too bright crops commander, and General of Cavalry Ebergenyi. Eugene’s favorite was the gifted Count Florimund von Mercy, whose main shortcoming was that his own career was marred by bad luck.16

Damad’s huge and motley army closed in on Peterwardein

The time taken by Eugene allowed the slow moving Turkish army to reach Belgrade. Grand Vizier Damad Ali Pascha took nearly three months to cover the 440 miles from Istanbul with his 120,000 strong Turkish Army. The elite Janissary ‘Ocak’ corps had not fully recovered from the defeat inflicted upon by Eugene at Zenta, but still made up some 40,000 infantry of the total host. Another 30,000 were Spahis, paid professional Ottoman cavalry.17 Tartar, Wallachian, Egyptian and various Asiatic auxiliaries made up the remainder of the Ottoman army. Though the Tartars were superb raiders, they and the rest of the auxiliaries were of doubtful value on the battlefield. Many of them still fought with outdated weapons like bows and arrows. Indeed the distinction between many ‘auxiliaries’ and the additional tens of thousands of camp followers, who had no combat value whatsoever, was blurred.18

With the wheat ripening in the summer heat and his army’s supply ensured, Damad set out from Belgrade. Typically breaking at dawn and making camp at noon, the Ottoman army crossed the River Sava on 26th and 27th July. Their vanguard probed towards Habsburg held Karlowitz, beyond which lay Damad’s objective of Peterwardein. Imperial scouts reported that the Turks were closing. Based on their reports, on July 28 Eugene wrote the emperor that the entire enemy host numbered 200,000 to 250,000 men- a considerable overestimation.19

Count Pálffy led a reconnaissance and was ambushed

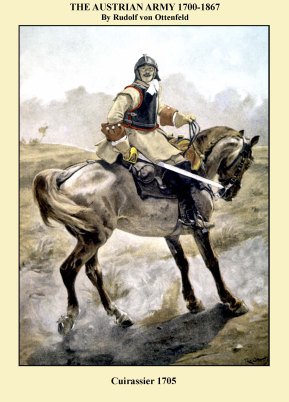

Count Pálffy volunteered to lead 900 Austrian cavalry, 400 Hussars (light cavalry) and 500 infantry on a reconnaissance. Eugene hesitantly approved but only after he explicitly ordered Pálffy to avoid any engagement. At night of the same day, Eugene received word from that Pálffy requesting reinforcements. Eugene sent out two more cuirassier regiments and again warned Pálffy to avoid any fight. Pálffy had little choice, however. On August 2, shortly after the cuirassiers joined Pálffy, over 10,000 Turkish cavalry took him by surprise. The location was near the chapel where the Peace of Karlowitz was signed in 1699.20

The battle that ensued raged for four hours as Pálffy desperately fought his way back to Peterwardein through difficult terrain cut up by trenches and hollows. Two horses were shot out from under Pálffy. Among the wounded were Lieutenant Field Marshal Count Hauben and Oberstleutnant Freiherr von Owen. Lieutenant Field Marshal Count Siegfried Breuner’s horse was also killed and he was captured by the Turks.21

At dusk Pálffy’s company could see the walls of Peterwardein ahead of them in the gathering gloom. The Turks were so close on Pálffy’s heels that his men could probably hear the ground rumble beneath the hoofs of the Spahis’ steeds. Ahead there were chaotic shouts. Soldiers ran here and there, forming a firing line as the fortress walls lit up with the flashes of cannon fire. Only then did the Spahis reign in their sweat-covered steeds and beat a hasty retreat.22

Pálffy had made it back by a hair’s breath, having lost seven hundred killed. Eugene conceded that the fiasco should not have happened and the less said about it the better.23

Eugene redeployed his army to confront Damad south of Peterwardein

In the meantime, Eugene built used a bridge of boats to move his army over the Danube. Then on the night of August 4t/5, he deployed it in a new positioned south of Peterwardein. The soldiers occupied an entrenchment left from a battle that occurred outside Peterwardein’s southern walls 22 years previous. Eugene had originally hoped to take Belgrade, but Damad had to be dealt with first.24

The Grand Vizier pushed on toward Peterwardein, where he found Eugene’s army awaiting him in front of the fortress. The Turks encamped south of Peterwardein, on the escarpment of the Frusta Gora. Under the protection of a barrage of Turkish heavy guns, the Janissaries dug trenches to within 50 paces of the Imperial lines and deployed in a huge half moon formation, engulfing the whole Imperial camp. Sporadic artillery fire erupted from the Imperial side.

Orta Imams (battalion chaplains) recited holy prayers to Allah an hour before sunset. Though the Janissaries were devout Muslims and technically the ‘slaves of the sultan’, most followed their own unique brand of Sunni Islam known as the Bektasi dervish sect. The more tolerant Bektasi beliefs incorporated old Turkish pagan, Buddhist, Shia, Kurdish Yazidi and even Christian elements, and appealed to the Janissaries who were of multicultural origin. Regardless of their religion, on both sides soldiers no doubt prayed that God grant them victory over the unbeliever.25

Elated by his minor victory over Pálffy, Damad immediately demanded Peterwardein’s surrender. He received no answer from Eugene, who from his own tent could see the Vizier’s pompous pavilion across the lines. It was part of a vast tent city erected by an army over twice the size of his own.26

In light of such adversity, Eugene’s officers urged him to fall back into Peterwardein or at least remain in the current entrenchment. Others even advised a retreat back over the Danube. Their mutterings faded into the background as Eugene drifted into his own thoughts. A morass to the left and a steep precipice to the right flanked Eugene’s current position. The fortifications of Peterwardein were even more formidable. But to hide behind walls and to let his soldiers’ morale wither away like the walls of the fortress? That was not Eugene’s way.27

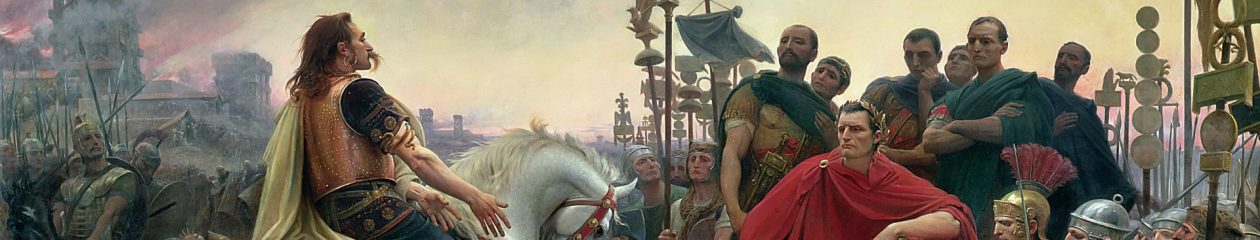

Eugene had fought the Turks for many years. The span was great: from the huge 1683 relief battle of besieged Vienna- when as a young man he had joined the emperor’s army with nothing more than a sword and his steed- to the end of that Second Turkish War, when he, now a Field Marshall, crushed the Ottomans at Zenta. Eugene knew that almost nothing could withstand the initial rush of the Turkish juggernaut. But once committed, or taken by unorthodox tactics, the Turkish army quickly lost discipline and control. Eugene would do what no one expected. Taking a deep breath, he spoke three words, “we will attack!”28

Eugene spoke three words, “we will attack!”

Eugene, however, did not rush into action. In typical manner he soundly worked out the battle plan for his 64 battalions and 187 squadrons. His battle scheme’s 31 points went into such detail as suggesting, that if called upon to fight in close combat, the commanders should ask their infantry to ditch their cumbersome jackets. Every infantry man was issued 50 bullets, every cavalry man 25 bullets, and every grenadier four hand grenades. The grenade, albeit in simplistic form, had already been in use since the 15th century.29

Eugene deployed the bulk of his infantry behind the foremost entrenchment in three lines under the command of Heister. Max von Starhemberg commanded the right wing of the first line, Feldzeugmeister (Quartermaster-General) Regal on the left. The second line was under Feldzeugmeister Prince Bevern and Count Harrach. Holding the third line as a reserve was Feldzeugmeister Freiheer von Lõffelholz.30

Outside of the entrenchment and to the left and front of the main lines, Prince Alexander von Württemberg commanded another six infantry battalions of 700 men each. Behind him was Count Pálffy’s cavalry, including Mercy, Ebergenyi and others. A storm played havoc with the ship-bridge and delayed the arrival of some last minute infantry and cavalry, which were still on the right Danube bank, but at 7 am, on August 5, all was ready.31

Von Württemberg opened the battle with rousing success. The Turks were momentarily stupefied, unable to comprehend that Eugene was taking the fight to them. With virtually no opposition Württemberg seized the Turkish trenches and a battery of ten guns lying ahead of him. Turkish footmen streamed away from his battalions and into them rode Pálffy’s cavalry, armored Austrian cuirassiers and Hungarian and Croat Hussars in their flamboyant attire.32

The Janissary advance threatened to collapse the Imperial center

Things did not go so smooth for Eugene’s center, however. In order to prevent them from being attacked while they were forming their ranks, Eugene had deployed his infantry behind the outer entrenchment. Now, however, as Heister’s infantry moved forward, the entrenchments broke up the lines. At this opportune moment Damad released his soldiers. In “ unbelievable fury”, as Eugene put it, and with thunderous bellows the Janissaries poured forth at the Imperial center.33

Damad stood at his tent, beneath the green holy banner of the Prophet fluttering in the wind. He gleefully watched as the lines of pearl-gray Imperials reeled before his red-clad Janissaries with their elaborate turbans or their typical white ‘Börk’ hats. Fired up by the bombastic clamor of the Ottoman Mehterhane military band’s huge kettledrums, clarinets, trumpets and cymbals, each Janissary fought as an individual. He considered the infidel’s way of “fighting like robots rather than warriors.”

Ottoman müskat tüfenkleri (flintlock muskets), pistols, Yatagan (reversed-curved swords) and two-handed axes took their toll on the soldiers of Starhemberg and Regal’s line, which wavered, fell back and threatened to collapse. Even the battalions of Bevern and Harrach’s second Imperial line took to flight. Sixteen Imperial standards fell into Turkish hands.34

Disaster was temporarily averted with the appearance of Imperial cavalry. The dashing cuirassiers, in ridged helmets and black bullet-tested breast and back plates, stopped the Janissaries in their tracks. From behind the Imperial horsemen boomed, Peterwardein’s guns, their shot ripping into the Turkish lines.35

With cavalry support von Württemberg swung inward to strike the Turkish right flank

In contrast to Damad, Eugene rode around the battle on his white charger. At times he could be seen in the foremost ranks, where he assessed the situation and gave quick and vital orders when needed. Calm and in control, Eugene observed that in the heat of the battle the Turks had neglected their flanks.36 He noticed that Württemberg ‘s advance had continued unabated. Sabers flailing and horses rearing, Spahis gathered to throw back the Imperials, but they shattered against Eugene’s stout Austrian cuirassiers coming at them in tight order. With the Spahis fleeing the field, Württemberg diverted to swing inward and strike the Turkish masses in their right flank. Eugene deduced that the decisive moment in the battle had arrived. He quickly gathered several thousand cuirassiers and sent some galloping to Württemberg’s support while others, under Ebergenyi, spurred their horses against the Turkish left flank.37

The Imperial infantry took new heart when Eugene himself rallied their fleeing troopers. Flintlock muskets cracking, bayonets fixed and supported by Lõffelholz’s reserves, the Imperial lines moved forward once more. Still watching the battle, Damad frowned and his thoughts turned to prayer. Attacked from three sides, his Janisssaries valiantly defended their ground until the pressure became too much. Order went to hell; it did not matter if it was an elite Janissary or some unwilling Wallachian auxiliary, each soldier sought only to escape the Imperial vice. Tearing through the panicked Ottoman horde, the cuirassiers’ carbines and pistols blazed, and their basket-grip, straight bladed heavy ‘pallasch’ sabers were flashes of crimson speckled light.38

Seeing his soldiers in headlong flight, Damad grasped his saber, swung onto his horse and bolted at the infidels at the head of his Agas. Yet fate did not reward his bravery. An Imperial musket ball hit him square in the forehead, knocking him off his horse. Incredibly, the wound did not instantly kill Damad. Dying he was whisked off to Karlowitz, there to be strangled by order of a furious Sultan. Also killed at Peterwardein were the governors of Anatolia and Adana, Türk Ahmed Pasha and Hüseyn Pasha, respectively.39

The wild pursuit of the routed Ottomans carried on through their artillery, their tents and their baggage. Close to noon, Eugene arrived at the Vizier’s tent where he beheld a horrific sight. There lay the corpses of 200 murdered Imperial prisoners. Among them the mutilated and beheaded Count Breuner, captured in Pálffy’s earlier cavalry engagement. Blood still poured from Breuner’s wounds and chains still bound his neck and feet. Such cruelty however, was not limited to the Turks; Eugene later impaled Turkish spies found among his Serbian troops.40

“The field being strew’d with the skulls and carcasses of unbury’d men, horses and camels”

The Imperials claimed 30,000 Turks killed for a loss of 3000 dead and 2000 wounded of their own. The Ottoman high number likely included countless camp followers indiscriminately hacked down in the chaotic rout. In the words of one of Eugene’s officers, “We took no more than twenty prisoners because our men wanted their blood and massacred them all.” The Janissaries, the only Ottoman troops that fought with skill and elan, probably suffered between 6000 and 10,000 casualties. Those of the Spahis, who fled the battle and abandoned the Janissaries, were minimal. Seven months later the renowned English writer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu visited the battlefield and recalled that “the marks of that glorious bloody day are yet recent, the field being strew’d with the skulls and carcasses of unbury’d men, horses and camels.”41

The loot was unbelievable. An eyewitness described the Turkish tent-city, with its multicolored pointed roof pavilions as a “gigantic flower-bed full of every kind of blossom.” There were 172 cannons, 156 banners and 5 prestigious horse-tail standards, gemstone studded weapons, Persian carpets, fine fabrics and an array of other treasures and thousands of wagons and tents, camels and horses. It took three hundred carts three days to carry it all away. A historian of the times noted that “if the spoils had been sold at their full value, and the money distributed amongst the soldiers, they would have had enough to have lived upon comfortably for the rest of their lives.” The Turkish war chest was discovered early by a couple of Imperial troopers who greedily filled their knapsack, their shirts, and even their hats. The holy banner, though, escaped the Imperial clutches and was safely brought to Belgrade.42

In Damad’s magnificent tent, surrounded by the Vizier’s treasures, Eugene wrote his dispatch to the emperor. The tent was so large that it had required 500 men to set up. Eugene claimed the tent as his prize, everything else he left to his soldiers. It was his soldiers, not himself, whom Eugene praised in his dispatch alongside, “God the all mighty… who blessed the Imperial arms with which the enemy was completely knocked out.” To minimize disease outbreaks, Eugene made sure his soldiers left the battlefield as soon as possible.43

The jubilation of Eugene’s victory spread from Vienna to Rome

On Eugene’s order, three hundred canon cannon salvos heralded his victory throughout the countryside. Eugene’s young regimental cavalry commander, Count Ludwig Khevenhüller, who had distinguished himself during the battle, rode to Vienna to deliver the news to the emperor. On August 8 when Charles VI got Eugene’s message the normally stiff emperor could barely contain himself with joy. All of Vienna danced with joy and Khevenhüller was mobbed with people who wanted to hear the story again and again.44

Emperor Charles VI promised Eugene substantially more financial war aid. The jubilation spread to Rome where every Church bell rang in Eugene’s honor. A grateful Pope sent Eugene a blessed violet biretta trimmed with ermine, decorated with a dove figure and embroidered in pearls, and a gem-encrusted sword and scabbard as long as Eugene himself. Even from France there were congratulations. Marshall Villers, who himself had once been bested by Eugene, praised the Imperial army and prophesied that Eugene’s campaigns would take him to the shores of the Black Sea.45

With little time for accolades, Eugene pressed on to take Temesvár

Eugene had little time for his accolades or the Pope’s sincere, if not ridiculous gifts. It was already too late in the season to consider an assault on Belgrade. Instead, on August 13-14th, Eugene left Peterwardein and pressed on toward Temesvár, the capital of the Banat of Temesvár. Pálffy and some infantry regiments and cavalry had been sent ahead to cut off the fortress-city’s supply line.

Eugene had his men march mostly at night to avoid heat exhaustion. One of the men described the campaign as “far more tiring and arduous than on the Rhine or in the Netherlands.” The Imperials reached Temesvár on August 26th. The operation showed Eugene’s logistical knack, as 80 guns and 30,000 hand grenades were brought over from Vienna alongside a 70,000 daily bread ration.46

Temesvár was the last remaining Turkish fortress in Hungary and had been in their hands since 1552. They nicknamed it the ‘Gazi’ (victorious) fortress. It had new fortifications built by 13,000 Wallachians forced into labor after they were unable to pay their taxes to the Ottomans. A river and a marsh gave further protection.47

Mustafa Pasha defended the stronghold with ten to fifteen thousand elite troops. They likely included Albanians and Bosniaks, reckoned among the toughest soldiers in Ottoman service. When asked to surrender, the valiant Mustafa Pasha retorted that Eugene may well have taken fortresses stronger than Temesvár but it was Mustafa’s duty to hold to the end for the honor of the Sultan.48

The siege commenced until nearly a month later, on September 23 a relief force of 20,000 Turkish cavalry arrived. Four thousand of the Turkish horsemen carried a second ‘Janissary’ rider, who presumably jumped off to fight on foot. Three Turkish assaults on the imperial defenses of von Pálffy’s encampment were all defeated and finally driven off by Max von Starhemberg’s resilient defense. They left behind 4000 dead.

On October 1st Prince Alexander von Württemberg’s Imperials breached the Turkish trenches and moat and penetrated into Temesvár. Nevertheless although the defeat of the Turkish relief force dashed Mustafa Pasha’s hope for victory and the Imperials were drawing ever closer, Mustafa Pasha refused to submit. Even Eugene was beginning to despair. Autumn rains filled the trenches and Imperial casualties already amounted to 2407 dead and 4190 wounded. Finally on October 13, after relentless Imperial bombardment and an imminent uprising by Temesvár’s citizens, Württemberg beheld a white flag on one of the towers. It was over. The city itself had suffered horribly, with its largely wooden houses burnt to the ground.49

During the battle, the fortress commander’s son was seriously injured. When Eugene heard of it, he sent a surgeon to help. The Turks in turn sent a younger son as hostage and a gift of six horses. Such chivalry, sadly rare in the otherwise brutal Turkish wars, further marked Eugene’s remarkable treatment of the defeated.

An honorable surrender by Mustafa Pasha

Eugene allowed Mustafa Pasha and his remaining soldiers an honorable retreat to Belgrade. Muslim families could depart with all their belongings, wagons, horses and livestock. Monies and supplies were given to reduce their hardships. Serbs, Jews, Armenians and Gypsies could chose to stay or leave as they wished. Eugene’s answer to Mustafa Pasha’s request that the Hungarian rebels who had fought under the Turkish banner be allowed safe passage as well: “ the rabble can go where it wants.”50

The Banat now lay at Charles VI’s feet but it was Eugene who successfully initiated its recovery from long years of war and desolation. Craftsmen and peasants arrived from Germany, enticed by subsidized travel costs, land grants, free tools, fuel, corn seed and six years tax exemption for craftsmen. Temesvár was rebuilt and earned the nickname of ‘little Vienna.’51

The effects of Eugene’s victories in 1716 rippled through Eastern Europe. In the churches of Wallachia, the people and the bishops prayed for Austrian deliverance from the Turkish yoke. All winter long, Imperial raids struck into Bosnia, Serbia and Wallachia. The fall of the Banat was not lost on the Turks either. Ottoman Grand Admiral Kapudan-Pascha broke off his lengthy naval siege of the citadel on Corfu. The Porte suddenly talked of peace and found support from the English, who wished to curtail Imperial power. But Eugene would have none of it and Charles VI followed his advice.52

After setting up the frontier guards and leaving Count Florimund von Mercy in charge of the Bant, Eugene returned to Vienna for the winter. There followed numerous festivities in his honor but Eugene was rarely seen at any of them. While the nobles, laughed, ate and danced beneath in their Baroque palaces, his thoughts were ever toward the southeast. The war was not yet over and next year he would strike at the prize that so far had eluded him, Belgrade.53

“We will attack,” Prince Eugene at Peterwardein” by L. H. Dyck was originally published in the August 2005 issue of Military Heritage Magazine. The above version has been reedited by the author and includes additional images sourced from the net for educational purposes only.

Notes

1. Henderson. Nicholas p.43, Mckay Derek p. 27, Dupuy and Dupuy p. 583, 2. Mckay Derek p.47, Fuller p. 519, Windrow and Francis p. 90, 91, Strayer, Gatzke, Harbison, Dunbaugh p. 451, 3. Fernec and Bernard p.288, 291, Wolfram p. 156, Bromley p. 629, http://www.4dw.net/royalark/Turkey/turkey7.htm, 4. Fernec and Bernard p. 294, Bromley p. 634, Mckay p. 161, 5-7. Kossak-Raytenau p. 162-164, Henderson p. 222, 223, Buchmann p. 170, Setton p. 432-434, 8. Setton p. 432, Henderson p. 223, 9. Kroener p. 121, Fernec and Bernard p. 292, 10,11. Setton p. 432, 433, Mckay p. 158-160, 12. Setton p. 434, Mckay p. 160, 161, Wolfram p. 156, Salten, Felix p. 58, 13. Kossak-Raytenau p. 168, Mckay p. 161, 14. Lindsay p. 175, 176, Barker p. 175, Coxe p. 100, 15,16. Lindsay p. 175-177, Kossak-Raytenau p. 165, 166, Henderson p. 42, 17. Mckay p. 161, Nicolle p. 7, 9, Kroener p. 121, 18. Henderson p. 223, 19. Setton p. 435, Kroener p. 121, Wolfram p. 156, Henderson p. 161, 20-23. Setton p. 435, Kossak-Raytenau p. 166, 167, Priesdorff p. 59, 24. Broucek p. 150, Kossak-Raytenau p. 166, Priesdorff p. 59, 60, 25. Priesdorff p. 60, Kossak-Raytenau p. 167, Nicolle p. 26, 29, 30, http://klaus.kempf.bei.t-online.de/Eugen.htm, 26,27. Kossak-Raytenau p. 167, 168, 28. Henderson p. 223, Kossak-Raytenau p. 168, Mckay Derek p.11, 29. Setton p. 435, Wolfram p. 156, Kossak-Raytenau p. 169, http://va.essortment.com/handgrenadeh_rgor.htm, 30,31. Kossak-Raytenau p. 169, 170, 32. Kossak-Raytenau p. 170, Setton p. 436, http://klaus.kempf.bei.t-online.de/Eugen.htm, 33. Bibl p. 206, Priesdorff p. 60, 61, Kossak-Raytenau p. 170, 34,35. Priesdorff p. 60,61, Kossak-Raytenau p. 172, Salten p. 102, Barker p. 169, 170, Nicolle p. 20-22, 31, 54, 36-38. Salten p. 102, 104, Bibl p. 206, Priesdorff p. 61, Kossak-Raytenau p. 171, 172, Barker p. 170, 39. Kossak-Raytenau p. 172, 173, Bromley p. 639, 40. Mckay p. 160, Kroener p. 124, Kossak-Raytenau p. 172, Priesdorff p. 61, 41. Setton p. 436, Henderson p. 224, Mckay p. 162, 42. Mckay p. 162, Henderson p. 224, Wolfram p. 156, Dupuy and Dupuy p. 642, 43. Setton p. 436, Henderson p. 224, Wolfram p. 157, Kossak-Raytenau p. 173, 44. Kossak-Raytenau p. 173, 174, Salten p. 105, 45. Salten p. 106, Henderson p. 225, 46,47. Henderson p. 226, Setton p. 436, 437, Wolfram p. 157, Mckay p. 162, http://albedoe.bei.t-online.de/tms23.htm, 48. Wolfram p. 157, Salten p. 107, Bromley p. 114, 49. Salten p. 107, Setton p. 437, Mckay p. 162, Kroener p. 123, 50. Mckay p. 162, Wolfram p. 157, http://albedoe.bei.t-online.de/tms23.htm, 51. Henderson p. 226, 227, 52. Sabel p. 98, 99, Henderson p. 227, Kossak-Raytenau p. 175, 53. Kossak-Raytenau p. 175, 176.

Sources

Barker Thomas M. Double Eagle and Crescent. New York: State University of New York Press. 1967, Bibl Victor. Prinz Eugen. Wien: Johannes Gunther Verlag. 1941, Bromley J.S. Editor. The New Cambridge Modern History. Volume VI. Cambridge: University Press. 1970, Broucek, Peter. Die Feldzüge des Prinzen Eugen in Ungarn, Italien and Westeuropa. Österreich und die Osmanen-Prinz Eugen und seine Zeit. Wien. Österreichisher Bundesverlag.1988, Buchmann M. Bertrand. Osterreich und das Osmanische Reich. Wien: WUV. 1999, Coxe William. History of the House of Austria. London: Henry G.Bohn. 1864, Dupuy Erenest and Dupuy Trevor. The Encyclopedia of Military History. New York: Harper & Row. 1977, Fuller J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World. Volume One. London: Paladin Grafton Books. 1988, Henderson. Nicholas Prince Eugene of Savoy. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. 1964, Kossak-Raytenau Karl. Prinz Eugenius Der Edle Ritter. Prag: Kaiser Verlag. 1942, Kroener R. Bernhard. Prinz Eugen und die Turken in Prinz Eugen von Savoyen und seine Zeit. Kunish Johannes. Freiburg: Ploetz Verlag. 1986, Lindsay J.O. Editor. The New Cambridge Modern History. Volume VII. Cambridge: University Press. 1970, Majoros Fernec and Rill Bernard. Das Osmanische Reich. Köln: Verlag Styria.1994, Mckay Derek. Prince Eugene of Savoy. London: Thames and Hudson. 1977, Nicolle David and Hook Christa. The Janissaries. Botley: Osprey Publishing. 2000, Priesdorff Kurt von. Prinz Eugen. Hamburg: Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt. 1940, Sabel von, Heinrich. Prinz Eugen von Savoyen. Munich: Verlag Georg D.W. Callmey Verlag. 1861, Salten, Felix. Prinz Eugen der edle Ritter. Berlin: Verlag Ullfstein &Co.1915, Setton. Kenneth M. Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. 1991, Strayer J, Gatzke H. Harbison E., Dunbaugh E. The Mainstreams of Civilization. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. 1969, Windrow Martin and Mason K. Francis. The Wordsworth Dictionary of Military Biography. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions LTD. 1990, Wolfram Herwig. Osterreichische Geschichte 1699-1815. Wien: Ueberreuter. 2001

Recommended Readings

Henderson. Nicholas Prince Eugene of Savoy. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. 1964, Mckay Derek. Prince Eugene of Savoy. London: Thames and Hudson. 1977, Nicolle David and Hook Christa. The Janissaries. Botley: Osprey Publishing. 2000,Setton. Kenneth M. Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. 1991.