Charlemagne: Warlord of the Franks

With warrior skills learned at his father’s side, Charles the Great—Charlemagne—carved out a mighty empire in strife-torn western Europe

by Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

On Christmas morning, 800 AD, a tall and lean man walked up the steps of Saint Peter’s basilica in Rome. Highly pious but by no means meek, Charles, ruler of the Frankish empire, had come—so he thought—simply to attend mass. In his mid-fifties, Charles retained the characteristic vigor for which he was known, his muscles hardened by years of warfare and his two favorite pastimes, hunting and swimming. Charles usually preferred the blue cloak and cross-gartered leggings of his own people. Today, however, he had obliged Pope Leo III, who had asked Charles to wear a long tunic, Greek mantle, and shoes of Roman fashion. Despite his classical garb, Charles’ fair skin, golden hair, piercing blue eyes, and great height marked him as a man of the cold, gloomy northern realms.

If Charles had had any inkling of the elaborate ceremony about to take place, he likely would have avoided the entire affair. He was a no-nonsense sort of individual, a man more accustomed to giving orders than to taking them. But as a scrupulously practicing Catholic, he felt it his duty to obey a summons from the Pope, even one who had a good deal more reason to obey Charles than the Frankish king had to obey him.

“The Most Pious Augustus”

Once inside the church, Charles was surprised and somewhat taken aback by the emotional greeting accorded him by the Pope. Leo, having barely escaped imprisonment and mutilation by his political enemies on spurious charges of perjury and adultery, owed his recent reinstatement to Charles. Charles had publicly shown his support of the Pope and demanded that he be restored to his seat as bishop of Rome. Now the grateful Leo returned the favor by placing a golden crown on the king’s startled head while the entire congregation cried out a blessing: “To Charles, the most pious Augustus, crowned by God, mighty and pacific emperor, life and victory!”1 After 324 years, there was once again an emperor in the West—not that Charles, better known to history as Charlemagne, needed a papal decree to make him emperor. He had already been one in fact, if not in name, for many years.

Through Charles’ great heart pumped the blood of the Franks, one of the major Germanic tribal groups. Centuries earlier the Franks poured into Roman Gaul from their homelands on the lower Rhine. The western Roman Empire was in its death throws and the great migrations were in full swing. Axe wielding Frank infantry, mailed Goth cavalry and fearsome Hun archers, among a colorful array of tribes, carved up the carcass of the western empire. The final act came in 476 AD, when Odoacer, a half Germanic, half Hun, barbarian general, disposed the last of the West Roman Emperors and became king of Italy.

In northern Gaul, King Clovis (c.465-511) consolidated the Franks’ hold on on the land through a combination of force and deceit. Although born a pagan, Clovis’ shrewd mind saw the Catholic Orthodox Church as a potential ally and unifying force. Clovis allowed himself to be baptized, along with thousands of his troops.

The Merovingian Franks are usurped by the Carolingians

Hedonistic excesses inevitably sapped the vigor of Clovis’s dynasty, the long-haired Merovingians. Their power gradually gravitated into the hands of their leading officials, the Arnulfing, or as they later became known, the Carolingians. The most famous of these usurpers was Charles Martel—the Hammer—who in 732 repulsed a Moorish invasion of Europe at the Battle of Tours and henceforth was immortalized as a savior of Christendom.

Martel’s grandson, eight-year-old Charles, must have looked up to his grandfather with awe. Born out of wedlock, Charles was the oldest of three children born to Pepin III, known by the unflattering nickname Pepin the Short, and to Bertrada of Laon. While his father was disposing of the last of the Merovingian kings in 751, Charles was learning from grizzled veterans how to use the weapons of war—the spear, the round shield with its heavy iron boss, the single-edged short sword, and the most powerful weapon of all, the double-edged long sword. It was a skill that would stand him in good stead in years to come.

The western Europe of Charles’s youth was fragmented by tribal rivalries, the growing power of the Catholic Church, the encroachment of Islam, and the waning influence of the Byzantine Empire. All these factions jockeyed for advantage and territory. In 754 a tear-stained Pope Stephen II threw himself at Pepin’s feet and begged for his aid against the “most evil Lombards.”2 Stephen was hoping that Pepin would help the Church retain its tenuous hold on Rome and the rest of Italy. At the time, the most prominent power in Italy was Lombard King Aistulf, who had just swallowed up the last Byzantine lands around Ravenna and was threatening to do the same to Rome. Aistulf swore that the he would butcher all the Romans unless they submit.

Honoring the Franks’ Ancient Alliance

Fortunately for the Church, Pepin decided to honor the Franks’ ancient alliance, which went back to the days of Clovis. Pepin not only wrested the Byzantine lands away from the Lombards but, instead of handing them back to their rightful owner, the Byzantine emperor, he gave them to the Church instead. In gratitude, the Pope anointed Pepin and his sons, Charles and his younger brother Carloman, as his rightful heirs.

Besides the Lombards, Pepin also fought Saxon and Moorish raiders. More often than not, Charles was at his father’s side. After a lengthy campaign, the Gothic kingdom of Septimania (Mediterranean France) was conquered and subdued in 759. Thereafter, the renowned Goth cavalry became a loyal Frankish ally. The rebel kingdom of Aquitaine, however, gave Pepin more trouble. During the eight-year-long Aquitaine War, Pepin’s Bavarian vassal, Duke Tassilo, refused to send any help, thus beginning a long feud between him and the Carolingians. Pepin, preoccupied by the fighting in Aquitaine, was unable to resolve the feud and bring Tassilo back into line.

When Pepin III passed away in 768 his Kingdom was split in Frankish tradition among his two sons. Right away, Charles was faced with a falling-out with his brother and with renewed rebellions in Aquitaine. Egged on by court flatters, Carloman resented having to share his father’s lands with a “bastard,” and refused to help his brother in Aquitaine. Like his father, Charles was left to fight in Aquitaine alone. Charles nevertheless drove the rebel leader into Gascony, whose duke not only surrendered the fugitive, but also submitted his province to Charles. Carloman was infuriated by his brother’s success.

In 770, Charles married the second of his five successive wives, Desiderata, daughter of the Lombard King Desiderius. Engineered by Charles’ mother, it was an effort to smooth out the traditional enmity between Lombards and Franks, but it failed miserably. The Pope was outraged, cursing the union with the “perfidious and foully stinking race of the Lombards.”3 Charles was none too happy himself. Claiming that Desiderata was ill and barren, he sent her back to her insulted father within the year. Relations with the Lombards soured further after Carloman suddenly fell ill and died. When Charles annexed Carloman’s kingdom, Desiderius sheltered the anti-Charles nobles of Carloman’s court, along with Carloman’s wife, Gerberga, and his infant sons. Together, Gerberga and Desiderius hatched plots to check Charles’ growing power.

In 772, Desiderius made another grab for the Papal States and tried to bully the Pope into declaring that Carloman’s son, not the bastard Charles, was the true king of the Franks. Charles strove to resolve the situation without resorting to violence, offering Desiderius 14,000 solidi in compensation for the Papal lands. Desiderius foolishly interpreted Charlemagne’s goodwill as a sign of weakness and refused the offer.

It was late in the summer of 773 and the weather was soon to turn foul and cold, when Charles called for the “heerbann,” the mustering of the host at Geneva. Foremost among Charles’ warriors were his elite guard, the “scara,” made up of though, battle hardened Franks, in chain or scale mail armor, with iron coifs and helmets, greaves or vambracers. A scara’s full arms and horse were of enormous expense, costing 40 solidi or as much as over a dozen cows. The military value of mail was such that any merchant exporting mail shirts was forced to forfeit his property. Only the King, his lords and bishops, could afford such splendidly equipped warriors. The bulk of the soldiers, levied by the counts and equipped by their home villages, made due with a spear or a bow and a shield. Charles’ entire armed forces numbered an estimated 30,000 heavily armed cavalry and 120,000 local levies. Most of these were absorbed in garrison duty, however. The field armies probably usually numbered up to 12,000-men-strong though at times possibly reaching up to 35,000.

In a two-pronged attack, Charles’ Frankish warriors descended upon Italy. Charles led one column down the shoulder of Mont Cenis, while his uncle, Count Bernard, moved through the St. Bernard pass, thereafter named after the count’s patron saint.

Cold wind, rain and sleet whipped at the Franks, who drew their cloaks about them and lifted one weary leg after another. Around them, rocks and pathless ridges reared to misty skies and abrupt abysses plunged to unseen depths. The slowly moving columns, with their pack horses, leather-covered ox carts, and a wide array of herdsmen, cooks, carpenters and merchants, pushed steadily onward. When Charles’ column descended into the valley of Susa, the hardest part of the trek was behind it. The soldiers may have breathed a sigh of relief, but they soon saw to their dismay the powerful Lombard fortifications that stretched across the valley ahead. Prince Adelghis, son of Desiderius, had come to contest Charles’ entry into Italy. Undaunted, Charles ordered an immediate assault.

Charles takes the Iron Crown of the Lombards

With brawny arms lifting banners high and battle horns resounding, the Franks let loose a thunderous war cry as they tore down upon the Lombard parapets and towers. Lombard bows twanged and arrows thudded into shields and faces. Lombard swords hacked through shoulder bones, blood spurted from rend mail, and spears thrust and parried as the Franks tried vainly to scale the ramparts. Charles contemplated a retreat when, according to legend, a wandering minstrel happened by. The minstrel sang of a secret mountain pass that led to the rear of the Lombard lines. “What reward shall be given to the man who shall safely conduct Charles into Italy?” the singer wondered, “on paths where no spear will be hurled, nor shield raised against him?”4

Whatever the truth of the legend, Charles sent a detachment along a high trail, which afterward was known as “The Way of the Franks.” The next morning, Charles renewed his frontal assault. Suddenly, the Lombards heard the tramp of marching feet, the clatter of arms and the neighing of horses- not just in front of them but behind them as well. Outflanked, the Lombard army broke in wild panic, the Frank cavalry riding down the stragglers. Prince Adelghis had enough. He fled to Verona and from there eventually made his way to the safety of the Byzantine court.

Unlike his son, King Desiderius was not ready to give up yet. He abandoned Susa but rallied his troops for a last stand at Pavia. Meanwhile, Charles reunited with Bernard’s column and in October advanced unopposed onto the Lombard capital.

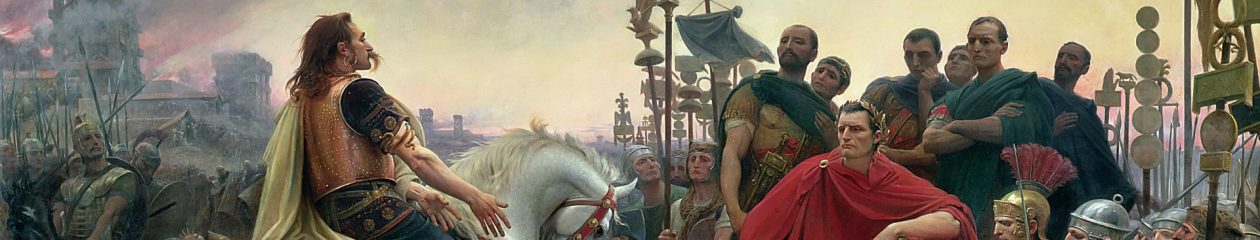

In fanciful prose the Monk of Saint Gall, one of Charlemagne’s biographers, captured the scene of Desiderius watching from a high tower. Beside Desiderius stood a noble who knew Charles in person. Both anxiously awaited the first sights of the approaching Frankish army:

First the baggage train appeared over the horizon. Desiderius asked, “is that Charles in the midst of that vast array?” “No, not yet” answered the noble.

Next the Frank army marched up, causing Desiderius to snap “now Charles is advancing proudly in the midst of his troops.” When this was still not the case, Desiderius flew into a panic, “ if even more soldiers come into battle…what can we do?

“There now appeared Charles’ escort followed by his abbots and their attendants. By this time Desiderius was sobbing, “let us go down and hide our selves in the earth, in face of the fury of an enemy so terrible.

“When you see the field bristle as with ear of iron corn…then you can be sure that Charles is at hand, ” said the noble and with those words, blew “from the west a mighty gale…the wind of the true north…which turned the bright daylight into frightful gloom.

“The Emperor rode ever on…topped with his iron helm, his fists in iron gloves, his iron chest and his Platonic shoulders clad in iron cuirass. An iron spear raised high against the sky” in his other hand “his unconquered sword.” “His shield was of iron, his horse gleamed iron colored” and all those who rode with him wore the same armor. “That is Charles,” exclaimed the noble to Desiderius, who “fell half conscious to the ground.”5

Charles counted upon his scara to breach Pavia’s defenses but in spite of the Desiderius’ apparent weakness, Pavia refused to submit. Lacking powerful siege equipment, Charles had to settle in for a lengthy investment of Pavia. A siege camp, including a chapel, grew up beneath Pavia’s mighty walls, graced by the arrival of Charles’ new young queen, Hildegard. Before winter passed, Charles found time to visit Rome, where he was given a triumphant reception. Roman soldiers lined the Flamian way, children waved palms and olive branches and sang hymns of praise to the puissant savior of the Church. Meanwhile, disease and famine wore down Pavia’s defenders until in June 774 the city fell to the Franks. Charles seized the Iron Crown of the Lombards and exiled Desiderius to a monastery. Charles’ conniving sister-in-law Gerberga and her children were found at the city of Verona and promptly handed over to Charles. Presumably they too ended their days in a monastery.

During his battles the Lombard cavalry impressed Charles so much that afterwards he made them the the spearhead of his army. The rising popularity of the stirrup in the 8th century transformed man, horse and lance into one massive projectile. Already since the 5th century, cavalry had been the backbone for most armies and now too the Franks were following suite. To lead the Lombard cavalry in the future and preside over the Carolingian Italian domains, Charles choose his second son by Hildegaard, Pepin. Already in 781, while on a pilgrimage to Rome, Charles had Pepin, who was still a toddler, crowned as King of Italy (r. 781-810).

Even though Desiderius was in exile at the Francia monastery of Corbiento, the feud of his family with Charles had not yet reached its end. One of Desiderius’ daughters, Liutberga, was the wife of Tassilo, the treacherous Duke of Bavaria, and she goaded her husband against Charles. Not that Tassilo need any prodding; what he needed were powerful allies. He looked to Italy, where half of the Lombard lands still remained in the hands of their dukes. There was no questioning the loyalty to Charles of brave Eric, Duke of the march of Friuli, or of Hildebrand, Duke of Spoleto, but Arichis, Duke of Beneveto, was another matter. Arichis eagerly allied himself with Tassilo and the two of them were further strengthened by the alliance of Constantine VI (r.780-797), the Byzantine boy-emperor who was still fuming because he had been denied Charles’ daughter in marriage.

In 888 Charles crushed the brewing conspiracy before it could get out of hand. He first dealt with the Lombard Duke Arichis who fled into the unconquerable fortress of Salerno from where he bend over backwards to appease Charles. To spare the people the ravages of war, Charles accepted Arichis overtures of peace and made Arichis’ son, Grimoald, Duke of Beneveto in his stead. As Byzantine envoys appeared to indicate a change of heart in their emperor’s stance against Charles, this left only Tassilo of Bavaria of the three conspirators. Having gained Papal support, Charles with his eleven-year-old son Pippin at his side, moved their army of Frank, Italian, Saxon and Thuringian soldiers upon Bavaria in a three-pronged assault. Tassilo, who had so contemptuously refused to acknowledge Charles’ suzerainty, panicked, surrendered, and was shipped off to a distant monastery. Bavaria was now under Charles’ control.

The Ring of the Avars

Before his fall, Tassilo had opened a new Pandora’s box by inviting the much-feared Avars across his borders. From their homelands in Turkestan, the Avars had migrated to settle in the old Roman province of Pannonia (Hungary), subjugating the local Slavs. Under their “Kagan,” the great Khan, they rapidly became a menace to their Slav, Germanic and Byzantine neighbors. For years even the Byzantine Emperor was forced to pay the Avars an annual tribute of an astounding 80,000 gold solidi. Although the Avar Khaganate came to extend over territory of modern-day Austria, Hungary, Romania, Serbia and Bulgaria, by the time of Charlemagne its zenith had passed.

In 782, swarthy Avar “jugars” (chiefs) with brightly colored strands interwoven into their hair, had visited Charles’ Royal and Military Assembly in Saxony. They talked of peace but Charles knew that the short, wiry Avars were as dangerous as hungry wolves, no different than his own Franks and the Saxons. If given the chance, they would sink their teeth into his growing empire.

In 788, with Charles busy subduing the troublesome Italian and Bavarian Dukes, the Avars saw their chance. They attacked Friuli in Lombardy but were unsuccessful, then advanced into Bavaria. Again they were defeated and their their terror-stricken warriors hunted down until they drowned in the Danube. After so many defeats, the Avars mused about the wisdom of having attacked Charles’ realm. In 790 their envoys came to Charles’ palace at Aachen to negotiate a mutually acceptable border with Francia along the River Enns. It was too late -the time for talk had passed.

The campaign against the Avar Khaganate was to be carried out by two armies. Charles would lead one down the Rhine, advancing from Bavaria, while a second army under Charles’ son Pepin, King of Italy (r. 781-810) would attack with the Lombards from north eastern Italy.

At the 791 Assembly, enthusiastic cheers greeted Charlemagne’s proposal to make war on the Avars. Charles assembled his army at Regensburg and from there advanced into the land of the Avars. On the bank of the Enns, Charlemagne held mass for three days, imploring “God’s help for the welfare of the army, the assistance of Lord Jesus Christ, and for victory over the Avars and revenge on them.”6

At his camp Charles received messages from Pepin telling him that he had already struck into Avar territory and on August 23rd won a great victory. Pepin’s Lombard cavalry was acquitting itself well against the Avar cavalry. It was during the Avar wars that the superbly trained Lombard cavalry established itself as premier shock troops. A prideful Charles wrote to his wife, “Our beloved son tells us that the Lord God gave them overwhelming triumph: so great a number of men have never been killed in battle.”7

Continuing along the Danube, Charles’ army of Franks, Saxons, Frisians, Serbs, Abodriti and Czechs continued on until near Vienna they reached the first Avar fortifications on both banks of the river. The Avars standing vigil on their fortifications in the wooded hills beheld the ominous sight of Charles’ great army, approaching on both banks, with a flotilla sailing in between them. God really did seem to be on Charles’ side that day, for Avars decided to abandon their defenses without a fight. They fell back to await the Franks at their legendary fortress, known as the “Ring of the Avars.”

Pepin meanwhile went on to captured the first or outer ring of Avar defenses and looted the villages therein. However, the appearance of Avar reinforcements prevented Pepin from advancing further. Pepin fell back, no doubt hoping to join his armies with that of his approaching father. However, Charles, had penetrated up to the river Raab when disaster struck. Pestilence broke out among the horses, devastating the cavalry. In addition the alarming news arrived of a palace revolution instigated by Charles’ neglected bastard son, Pepin the Hunchback. The Avar campaign was called off as Charles returned home, burning and killing along the way. Once back home, he squashed the Hunchback’s revolt and sent his deformed son to a monastery. Pepin, the king of Italy, delivered the treasures he had taken and 150 Avar prisoners to Charles at Aachen.

For several years Charles was kept busy by the Saxons (see Saxon Wars below) and other affairs. In 795, there surfaced the first indication of dissension among the Avars when the emissaries of the highest Avar “tudun” (Chancellor) appeared at Charles’ court at Aachen. The emissaries declared that the tundun wished to submit himself and his people and accept the Christian faith. The Avars had turned upon each other and were soon at each other’s throats. Civil war broke out, claiming the lives of both the Kagan and jugar.

With the Avars fighting each other, Duke Eric of Friuli sensed easy prey. In 796 Eric unleashed his Lombards under a Slav general named Wonimir. On the plains of Pannonia, armored Lombard and Avar horsemen sliced through each other’s ranks. Heavy lances powered through mail links and shattered shields. Avar horse archers sent arrow after arrow into the Lombard ranks, whose own bowmen trudged onward on foot. But the Avars were disunited and the Lombards shattered their famed Ring. The Ring went into legend as a gigantic, near impregnable, fortress of nine concentric rings of stone and clay, crowned with hedges and palisades. Modern opinion, on the other hand, holds that it more likely referred to a series of fortified earthworks surrounding Pannonia. Duke Eric of Friuli faithfully sent the vast Avar treasures to Charles.

That same year the tunus and his following received baptism but soon after broke their fealty. A second Frank army under Pepin King of Italy was needed to hold the Ring and secure the rest of the treasures. In all, 15 wagons loaded high with gold and silver coins, cloth of gold and precious ornaments rolled into Charles’ court at Aachen. A gratified Charles lavished gifts upon friends and allies and used the wealth to complete his magnificent palace and chapel. The Avars, however, were not entirely finished yet and sporadic fighting lingered on into 803 before their lands were incorporated into Charles’ empire.

The Saxon Wars

Even more savage than the Avar war was Charles’ war against the Saxons. By the end of the great migrations, the Saxons occupied most of northern Germany. Unlike most of the other Germanic peoples, they had never embraced Christianity and stayed true to the old gods and to the reverence of nature and trees. The Saxons were the most poorly equipped of Charles’ foes. Cavalry and armor were all but unheard of – a spear, an axe or, if he was lucky, a sword was all a Saxon warrior could count on. What the Saxons lacked in equipment, however, they made up in bravery, tenacity and unconventional warfare. A terrible cycle of raids and counter-raids was the order of the day along the Saxon-Frank border.

In 772, fuming with anger, a vengeful Charles crossed the Rivers Eder and Diemel. Deep in the Saxon heartland, at Eresburg, he destroyed the sacred, all sustaining pillar of the Saxons, the wooden “Irminsul.” There had been sacrificed to Othin eight different beasts and one man, hanged from branches, their blood soaking the earth of the Saxon holy site. There too, were treasures of gold and silver to enrich the Frankish war chest.

The Irminsul’s destruction only served to unite the Saxons under a powerful guerrilla leader, Widukind, whose vengeful warriors set fire to Frankish border villages and churches, looting, raping and killing at will. Everywhere, Frankish villagers fled in terror of the Saxon raiders. As soon as Charles’ heavily armed troopers arrived to fight the invaders, Widukind’s raiders took to the woods or melted back into the general Saxon population. Unable to come to grips with the partisans, Charles released his Franks on the hapless Saxon villages.

To establish order Charles built strongholds or captured them from the Saxons. The Saxons struck back, infiltrating a Frankish camp in 775 and butchering the sleeping and half-awake garrison. The following year the Saxon army demolished the Frankish stronghold at Eresburg but faltered at Syburg, which resisted both the clumsily built Saxons siege engines and the torch.

Nevertheless, Charles kept up the pressure and by 777 it was the Frankish banner which fluttered over many of the circular palisades, ramparts and moats that protected the strongholds of Saxony. Charlemagne deemed that the time had come to hold his annual Assembly in Paderborn, Saxony. The Saxons found themselves called to the “heerbann,” the mustering of the host, and there were mass baptisms. Even now, however, the Saxons’ eyes burnt with an unbroken will to retain their pagan freedom.

Widukind had fled to his Kinsman, the Pagan King of Denmark but returned to lead another uprising in 778. The following year the Franks tore through the Saxon ramparts at Bochult. In the aftermath of the battle, churchmen in lavish robes moved among dead and dying, chanting Psalms and giving last rites and lending aid to the handful of doctors. The clergy became a permanent fixture of the Saxon wars, as Charles further consolidated his hold on the land by establishing mission districts.

In 782, news arrived of Slavs raiders on eastern Saxon borders. Charles sent three high-ranking commanders, Adalgis, Geilo and Worad, to take care of the intruders. The three marched their soldiers the east, when to their horror their Saxon auxiliaries deserted in another massive uprising led by the elusive Widukind. When Charles heard this, he sent in reinforcements under his cousin, Count Theodoric.

The Saxons awaited the four Frank commanders on the slopes of Süntel Mountain. Theodoric ordered a pincer movement, much to the annoyance of the other three commanders. Confident that they did not need Theodoric’s help, Adalgis, Geilo and Worad attacked prematurely. With a blare of trumpets they spurred their cavalry up the slope, right into the Saxon lines bristling with spears. It was a slaughter. The Saxon ranks stood unbroken, the Frank cavalry a writhing mess of dying and trampled horses and men. Both Adalgis and Geilo, along with five counts and 19 other nobles, perished in the attack.

A raging Charles came storming back across the Rhine but once again the Saxon army vanished into the villages and forests while Widukind found safety among the Danes. Charles’ fury knew no bounds. In a grizzly bloodbath at Verden, 4500 Saxons were rounded up and beheaded. And if that did not prove his point, Charles ordered churches built near his Saxon military outposts. He ordered the death penalty for any Saxon who refused baptism or committed even the slightest transgression against Christianity.

The next few years saw incessant punitive raids, battles and castle assaults, as Charles pushed through Saxony and into the lands of the Slavs. Those Slavs that readily submitted, he treated as allies, the others were subject to the same brutalities as the rebellious Saxons.

In 785, Widukind, after defeats at Detmold and at Osnabrück, on the “Hill of Slaughter,” finally surrendered. He had enough of the bloodshed and accepted that the Christian god was stronger than Othin was. Widukind received his baptism at Attigny. As a sign of respect for his old adversary, Charles stood as Widukind’s godfather. With Widukind no longer an adversary, peace seemed assured. Yet even though they had lost their charismatic and skilled leader, the Saxons refused to bow to Charles’ Christian yoke. In 793, Saxon rebels ambushed and annihilated Count Theodoric and his entourage, reopening the war.

Charles’ final answer was forced deportations: seven thousand Saxons in 794, every third household in 797 and1600 leaders the next year. This finally did the trick, as increasing numbers of Saxons remained loyal and the centers of resistance shrunk to the eastern borders of their realm. In 804, 10,000 Saxons, the entire population east of the Elbe, were settled in Francia. Christianity had been hammered into the Saxons. After thirty years of war and resistance, the last embers of resistance flickered out. The Saxons learned their lessons well. Centuries hence their descendants, the Teutonic Knights, marched east to convert the pagan Baltic peoples at the point of the sword.

Charlemange’s Campaigns in Spain

Charles fought longer in Saxony than anywhere else but it was in Spain, where he fought arguably his most famous battle. Ironically, it was also his greatest defeat. During the 777 assembly at Paderborn, a deputation of exotic strangers caused much attention among the tall, fair-skinned Franks and Saxons. Suleiman ibn Al-Arabi, the governor of Barcelona and Gerona, had come to ask Charles for help against his rival, the Emir Abd al Rahman of Cordova. Suleiman was ready to hand over his own cities to Charles and promised that the governor of the key strategic city of Saragossa would do so as well. Charles liked what he heard, and in 778, over 40,000 Franks and allied Lombards, Bavarians, Burgundians, Provencals, Bretons and Goths crossed the Pyrenees to meet up at Saragossa’s gates. The enraged Muslims inside, however, refused to open the gates to an infidel. For a month Charles laid siege to Saragossa. Although Suleiman kept his word and submitted both Barcelona and Gerona to Charles, he was unable to offer any concrete help. Branded as a traitor to the Muslim cause, Suleiman was assassinated by an emissary of Abd al Rahman. Frustrated, Charles called off the siege and turned back home. On the way he let his anger out on the less fortified city of Pamplona, razing the walls and sacking the city.

Disaster befell the rear guard of Charles’ army on its way through the narrow pass of Roncesvalles. Hidden in the woods and shrubs lurked thousands of wild hill folk, the Basques. They patiently watched the Frank army march through the forbidding countryside. After a long wait, there appeared the rearguard with the baggage. The day was hot and the Frank soldiers huffed in their heavy mail and wiped rivulets of sweat from their brows. Suddenly, boulders came rumbling down the slope, crushing whoever was caught in their wake. Missiles whistled through the air, piercing shields, mail and flesh. With a roar, the lightly armed Basques swept down the slope. A furious, chaotic melee erupted. Frankish swords shattered Basque spears and splintered shields. But the Basques were too many. Overwhelmed, the Franks fought until the last man. Among the fallen was Roland, prefect of the Breton march. Darkness shrouded the crimson splattered, corpse filled, pass. The Basques looted the baggage and quickly disappeared into the night. The valor of Charles’ soldiers was later immortalized in the famous “Song of Roland.” In the song, the Basques are changed to Saracens and Roland becomes the brave hero, who blew the Oliphant horn in a desperate call for help.

The Spanish debacle of 778 was not the last time the Franks and Muslims crossed blades. The Muslim cities of the Spanish march continually tried to defect to the Emirate of Cordova and in 801 Barcelona only resubmitted after a two-year siege.

The turn of the century marked the end of Charles’ great conquests. Battles continued to rage on virtually every border of Charles’ realm, but they were for the most part wars of consolidation. Brittany rebelled repeatedly and was never really conquered. In the east, the withering of the Avar and Saxon wars gave way to escalating conflicts with the Slavs. Led by Charles’ namesake son, the Franks conquered the Sorbs and the Bohemians. In Italy, Charles’ second son, Pepin, King of Italy, was kept busy with the unfaithful Grimoald of Beneveto. Ortona and Lucera were besieged, and there were skirmishes with the Byzantines concerning Venice.

Charles rides to Battle for the last Time

With old age creeping up on him, Charles left most of the fighting to his sons and captains. He resided longer and longer at Aachen, which he loved due to its hot springs. He stayed busy with the administration of his empire.

The latest and most dangerous threat to Europe was the advent of the Vikings. From Norway, the sons of Odin hit the British Isles the earliest and the hardest. The Danes under King Godofrid likewise made war on Charles’ Slavic allies and raised a colossal rampart along the Danish-Saxon border from the Baltic to the North Sea. In 810, Godofrid’s huge fleet of 200 ships crushed the Frisians, who were part of the Saxons realm. Godofrid boasted that he could not wait to meet Charles in open battle.

For the last time, Charles mounted his battle charger. Even at nearly seventy years old, Charles, with his platinum hair and six-foot-tall gaunt frame remained a larger-than-life figure. Before the two forces could clash in combat, Godofrid was murdered by one of his retainers. His fleet returned home and his successor was eager to make peace with Charles. There would be much war to come between Vikings and Franks, but not while Charles still lived.

Charles’ Pan-European Empire

Charlemagne carved out the first pan-European empire, a feat that many future warlords, including Louis XIV the “Sun King,” and Napoleon, tried to emulate but could not. Charles lived in a brutal age and did not refrain from using overt violence to obtain his goals. Yet within his realm there was peace unknown since Pax Romana. Charles kept his soldiers on a tight leash, forbidding pillaging of the countryside and drunkenness. When possible, scouts marked out the route, warning the villagers of the cattle and sheep that would be requisitioned from them once the army passed through. Charles needed no walls to protect his villas, instead building monasteries, schools and a great bridge across the Rhine. He fostered the liberal arts and gathered to his court the intellectual elite of Europe in what became known as the Carolingian renaissance.

Charles’ ascendancy was not lost on the rest of the western world. There was correspondence with the Kings of the British Isle and with the Byzantines. For a time there was even a chance of Charles marrying the beautiful widowed Empress Irene. Harun-al Rachid, the opulent Caliph of Baghdad and enemy of the Spanish Emirate of Cordova, was Charles’ lifelong friend. One of his gifts to the great barbarian king of the north was an elephant named Abbul Abuz.

In 823, Charles personally crowned his remaining legitimate son, Louis the Pious, King of Aquitaine, as co-Emperor and successor. The crowning took place in Aachen and not in Rome. By this Charles made it clear that despite his own investiture by the Pope, it was Charles, not the Church, who choose his successor. Nevertheless, the Pope’s investiture of Charles as Holy Roman Emperor set a precedent that led to centuries of dissension between the Papacy and the Medieval Holy Roman Empire.

Originally, Charles had intended to split his Empire among his three sons but sadly both Pepin, King of Italy, and Charles the Younger, the conqueror of the Slavs, had died prematurely. Louis the Pious inherited his father’s love for learning but unlike his late brothers, he had none of his father’s warlike nature. When on January 28, 814, Charles succumbed to old age after 47 years as King of the Franks, Louis found himself unequal to the task of carrying on his father’s legacy. It was not long until feuds fragmented the empire forever.

Without Charles’ coalescing personality his empire was fated to collapse. In many ways Charles never saw himself as anything more than a great tribal warlord; his “empire” no permanent institution like that of Rome but an amalgamation of tribal kingdoms loyal to himself. The days of great empires were over anyway. The Medieval age had begun, which forever remembered Charles as the ideal king, the champion of Christ, the rex pater Europa (King father of Europe), source of glorious legends, as Charles the Great, Karl der Grosse, as “Charlemagne.”

Notes

1. Stephens, W. R. W., Hildrebrand and his times (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1988), p. 7. 2. Eduardo Fabbro, Charlemagne and the Lombard Kingdom That Was: the Lombard Past in Post-Conquest Italian Historiography (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association: Volume 25, 2., 2014) p. 5, 6., 3. Russel Chamberlin, The Emperor: Charlemagne (New York: Franklin Watts. 1986), p. 66, 70., 4. J.I. Mombert, A History of Charles the Great (London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co. 1888), p. 91., 5. Einhard and Notker the Stammerer. LewisThorpe , translator and Introduction, Two Lives of Charlemagne (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 1987), p. 162, 163., 6. Bernhard W. Scholz and Rodgers Barbara, Translators. Carolingian Chronicles, Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories (The University of Michigan Press. 1972), p. 69., 7. Russel Chamberlin, p. 177.

Sources

Bunson Matthew E. Encycolpedia of the Middle Ages. New York: Facts on File. 1995, Chamberlin Russel. The Emperor: Charlemagne. New York: Franklin Watts. 1986, Clark Kenneth. Civilization. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. 1981, Einhard and Notker the Stammerer. Thorpe Lewis. Translator and Introduction. Two Lives of Charlemagne. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 1987, Goldin Frederick. Translator. The Song of Roland. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 1978, Hildinger Erik. Warriors of the Steppes. New York: Sarpedon. 1997, Joshua J. Mark, Odoacer, Avars, Ancient History Encyclopedia., Keegan John. A History of Warfare. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1993, Mombert J.I. A History of Charles the Great. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co. 1888, Nicolle David. The Age of Charlemagne. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. 2004, Norwich John Julius. Byzantim the Early Centuries. London: Penguin Books. 1990, Parker Geoffrey. Editor. Warfare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1995, Russel Charles Edward. Charlemagne, First of the Moderns. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1930, Scholz W. Bernhard and Rodgers Barbara. Translators. Carolingian Chronicles. Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories. The University of Michigan Press. 1972.

Charlemagne “Warlord of the Franks,” was originally published in Military Heritage Magazine and republished on the magazine’s website, Warfare History Network. The above re-edited version contains additional images for non-profit, educational purposes only.