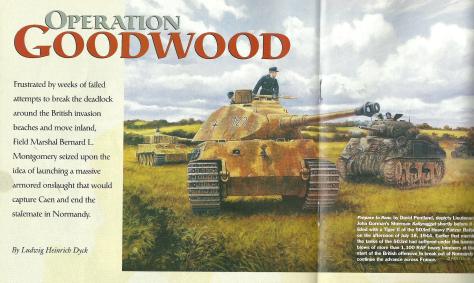

Epic Armor Clash in Normandy

“Operation Goodwood”

By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

Frustrated by weeks of failed attempts to break the deadlock around the British invasion beaches and move inland, Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery seized upon the idea of launching a massive armored onslaught that would capture Caen and end the stalemate in Normandy.

A burst from a titanic bomb flung the colossal 58-ton Tiger tank into the air and onto its back. Four Tigers of the 3rd Company 503rd Heavy Panzer battalion, virtually invulnerable to anything but artillery fire and air strikes, were knocked out in the orchard outside of the hamlet of Manneville. Others were smothered in earth that erupted from 30-foot deep bomb craters. Though sheltered in foxholes beneath the steel behemoths, the crews’ nerves snapped. One man went insane while two others committed suicide.

![Despite its 56-ton weight, this Tiger I of 3./s.Pz.Abt. 503 (3rd Company 503rd Heavy Tank Battalion) was overturned at Manneville by the bombing. Three men survived.[110]By Connolly (Sgt), No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ludwigheinrichdyck.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/the_campaign_in_normandy_1944_b8032.jpg?w=474&h=382)

Lieutenant Freiherr von Rosen remembered asking to himself “Will there never be an end to these explosions?” Later he remarked that “the bombing was the worst we ever experienced in the war…Of my 14 Tigers not one was operational. All had been covered in dust and earth, the guns dis-adjusted, the cooling systems of the engines out of action.”1

The 3rd Company’s troubles began on July 18, 1944, at 0525 hours with an with an artillery barrage that erupted on the German positions a few kilometers to the east-southeast of Caen. Ten minutes later there followed the drone of 1,100 British heavy bombers.

The British Twenty-first Army Group Chief of Staff, Freddie De Guingand, climbed on top a haystack to witness the spectacle: “It looked just like a swarm of bees homing upon their hives…One appreciated the great bravery of those pilots and crews as they flew into the most ghastly looking flak. Every now and then an aircraft would burst into flames and usually shortly afterwards a few parachutes could be seen making their way to earth.”2

British Avro Lancasters and Handley Page Halifaxes carpet-bombed with high explosives to suppress German anti-tank guns along the flanks of the planned British attack. At 0700hrs, 482 heavy and medium bombers of the US Eighth and Ninth air forces sought victims for their non-cratering fragmentation bombs along the central path of the British advance. Three hundred additional fighters and fighter-bombers swept down on German strong points and gun emplacements.

Huge clouds of smoke and dust from the explosions diffused into the hazy opal sky above the Norman countryside. Their view obscured, many pilots aborted their missions. Still it was not over. At 0800hrs, 495 Eighth Air Force heavy bombers pounded the German defenders. The day would see more than 4,500 Allied aircraft in action against the Germans east of the River Orne. Some 7,700 tons of bombs were dropped on the German lines, nearly half of them in less than 45 minutes. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, called it “the heaviest and most concentrated air assault hitherto employed in support of ground operations.”3

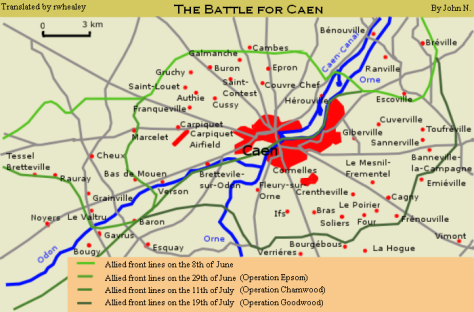

The allied air strikes were the prelude to Operation “Goodwood,” the latest in a series of British offensives against the German positions in the Caen area. Like the Americans on their right flank, the British had failed to make any decisive progress since early June, advancing at a snail’s pace and at the cost of high casualties and materiel. General Eisenhower blamed the stalemate in Normandy after D-Day on “first as always the fighting quality of the German soldier; second the nature of the country; third the weather.”4

Though watered down by low morale foreign troops, veteran Waffen-SS, Paratroop and Wehrmacht soldiers of the German Seventh Army made the tangled bocage, or hedgerow country, a nightmare for the U.S. First Army, while its Panzer Divisions squared off against Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army. Storms played havoc with Allied shipping in the channel. The Germans in turn faced the more serious problem of Allied air supremacy, which precluded all but night travel. If the Allies had failed to break out into the open country to the south, the Germans were likewise unable to hurl the invader back into the sea.

Goodwood was meant to break the stalemate in conjunction with Operation “Cobra,” an equally devastating American breakout on the Allied western flank, several days later. For Goodwood a vast bombardment would precede an overwhelming armored assault from the eastern side of Caen. The operation was the brainchild of Dempsey and found favor with Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, overall commander of Allied ground forces., who said, “the Second Army is now very strong…and can get no stronger…So I have decided that the time has come for a real ‘showdown’ on the eastern flank, and to loose a corps of three armored divisions into the open country about the Caen-Falaise road.”5 The objective of was “to engage the German armor in battle and write it down” to “destroy German equipment and personnel, as a preliminary to a possible wide exploitation of success.”6 Specific tactical objectives were the villages of Vimont, Garcelles, Hubert-Folie, Verrieres and Bretteville-sur-Laize, on the commanding Bourguébus Ridge.

Lieutenant General Sir Richard O’Connor’s VIII Armored Corps spearheaded the British Armored thrust, with its 11th Armored Division in the vanguard. The 11th was arguably the best British armored division, commanded by the very able Africa veteran, Major General “Pip” Roberts. At 37 years of age, Roberts was the youngest British divisional commander. After the 11th came Maj. Gen. Allan Adair’s Guards Armored Division with Maj. Gen. Bobby Erskine 7th Armored, the famed “Desert Rats,” bringing up the rear. With some 266 tanks, 361 scout and armored cars and 2,000 trucks in each division, the three together boasted over 8000 vehicles.

Covering the VIII Armored Corps’ left flank was Lt. General John Crocker’s I British Corps. To the right, General Guy G. Simmonds’ II Canadian Corps, in the joint operation dubbed “Atlantic”, hoped to oust the Germans out of southern Caen by attacking from eastern, central and western areas of the city.

At 0745 a creeping artillery barrage of 200 guns heralded the armored advance. Many guns fired more than 400 rounds but unfortunately some of the shells fell short of their target. The friendly fire killed and wounded a number of unlucky crews who enjoyed a last cigarette outside of their tanks. Major Bill Close, commander of A Squadron 3rd Royal Tank Regiment (3 RTR) 11th Armored, recalled “This happening a few seconds before we were to start, added considerably to the confusion, and we set off after the barrage in some disorder.”7

With an order of “Move now” the ground trembled, as the Shermans of the 29th Armored Brigade rumbled through the dust. With their crews’ vision obscured and the ground pockmarked by bomb craters, the tanks became jumbled and soon fell behind the advancing artillery fire. From the bridgehead south of the Orne River, the tanks continued in a narrow column, first through the cleared British minefields and then through a two-kilometer wide corridor flanked by the Caen’s factories to the west and a forest to the east. Beyond, a swath of flat and open ground, sprinkled with wheat fields and hamlets, lay before the main objective some 15 kilometers to the south, the Bourguébus Ridge.

To surprise the Germans, only the 11th Armored Division’s 29th Armored Brigade crossed the River Orne before H-hour. But the deafening thunder of so many tanks could not be covered up. Oberstgruppenführer (SS-Colonel General) “Sepp” Dietrich pressed an ear to the ground and heard the sound resound through the limestone of the Caen plain. It was a technique he had used many times before in Russia. The Germans also enjoyed a view over the whole Orne bridgehead from their positions in the Colombelles factories south of Caen. They knew something big was about to happen.

Facing the British-Canadian onslaught were the soldiers of Panzer Group West, commanded by Gen. Hans Eberbach. The Panzer Group was part of Army Group B, which in light of Rommel’s injury on July 17th was under the direct command of the commander of the western front, Field Marshal Günther von Kluge. Panzer Group West fielded 194 guns, 272 rocket launchers and 377 Panzers and self-propelled (SP) assault guns-far more than the Allies anticipated.

The Panzer Group was divided into two corps, with General Hans von Obstfelder’s LXXXVI Corps facing the British. The corps’ 346th Infantry Division was deployed from the coast to just north of Touffreville and out of the way of the main British-Canadian thrust. The opposite was true of the already badly mauled 16th Luftwaffe Field Division, deployed from Touffreville west to the Colombelles factories-right in the way of the British Armor.

The 16th Luftwaffe Field Division provided little more than a thin screen. The key division to hold up the British Armor was Lt. Gen. Edgar Feuchtinger’s 21st Panzer Division (PzDiv) of Africa Korps fame and its Kampfgruppe (battlegroup) Luck. Major Hans von Luck’s Kampfgruppe included the 1st and 2nd Panzer Grenadier (PzGr) battalions of his own 125th PzGr Regiment and Major Alfred Becker’s 200th Sturmgeschütze (StuG) battalion with 75mm SP assault guns and 105mm SP artillery. On the left flank of Kampfgruppe Luck, the 21st Division’s 192nd Panzer Grenadier (PzGr) Regiment augmented a Luftwaffe PanzerJäger (Anti-tank) battalion at the Colombelles factories. The 21st Division’s 1st Panzer Battalion and the independent 503rd Heavy Panzer battalion, including a few Tiger IIs, covered the right flank between Sanderville and Emviélle. A battalion of the 9th Werfer (rocket launcher) Brigade was also positioned near Grentheville.

On the German left wing, Panzer Group West’s I SS Pz Corps, led by SS Col. Gen. Josef “Sepp” Dietrich, awaited the Canadians. Dietrich had just received the 272nd Infantry Division to take over the forward position in Caen south from the exhausted 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. After very little recovery time, Hitlerjugend was ordered into reserve on July 16th. It had a Kampfgruppe stationed farther east at Lisieux, while the rest of the division was to the south, just north of Falaise. Unknown to the British, Dietrich’s other Panzer division, the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (LAH) was also in reserve, on and behind the western slopes of the Bourguébus Ridge with some of its units in additional corps reserve west of the Orne.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and General Heinrich Eberbach had ensured that Panzer Group West sported the deepest and toughest defenses in Normandy-at 12 kilometers deep, they were far deeper than the seven kilometer estimated by the Allies. Because of this, most of the vital German positions remained relatively unscathed by the Allied bombardment. These included the artillery and Nebelwerfers deployed behind Bourguébus Ridge. The remnants of the green 16th Luftwaffe Field Division, however, bore the full brunt of the bombardment and were virtually obliterated. Initial German prisoners taken were so stunned that they could not be interrogated for 24 hours. The general allied perception was “no one will survive this inferno. We need only march in with our tanks to open the way to Paris…how wrong we were.”8

At first though, things went smoothly for the British. As the British tankers drove by villages of Cuverville and Démouville, dazed, pallied German infantry wandered out of the wheat fields to surrender. At Démouville a Panzer Mark IV appeared and was promptly knocked out by the Shermans. Most German survivors remained stunned in their trenches. A few took potshots at exposed tank commanders. The tanks and motorized companies left them to be mopped up by the British infantry following behind.

The Mark IVs of the 1st Panzer Battalion stationed in the woods between Sanderville and Emviélle suffered severely under the bombardment. Although not many were complete write-offs, they were deluged with tons of soil, fouling their engines. The waves of Shermans shot up four of the Mark IVs and overran another five, capturing their startled crews. The Tigers of the aforementioned 503rd in the same area fared somewhat better. Those that could not be repaired were towed out, sometimes only minutes before the arrival of British tanks. No British Recovery units could move a Tiger anyway-in one instance it took three Tigers to tow one Tiger out! A number of Mark IVs and Tigers were repaired in the field by noon and thereafter harassed the British advance.

Colonel David Silvertop’s leading 3rd RTR reached the Caen-Troarn railway line at 0830. There was some confusion due to poor visibility and congestion as the 11th Armored’s other tank regiments, the 2nd Fife and Forfar Yeomanry, and the 23rd Hussars began to catch up with the 3rd RTR. Half an hour later the dull thumps of the artillery barrage ceased, leaving only a few 25-pounder SP batteries to support the British armor.

At Le Mesnil-Frémentel the ground began to slope upward to the Bourguébus Ridge. The 3rd RTR veered to the west, while the 2nd Fife and Forfar headed eastward and then south. From the wheat fields, Nebelwerfer rockets howled into the air, leaving long blue-white trails. The British tanks simply overran many of them. But as they did so the Shermans and their motorized company rolled into the gun optics of Becker’s 75mm SP assault guns hidden in le Mesnil-Frémentel and in le Poirier, which burst up a handful of Shermans from the leading squadron of 3rd RTR. The rear squadron of the 2nd Fife and Forfar lost another 12. To deal with the StuGs and their supporting grenadiers, the British needed more infantry but the 11th Armored Division’s 159th Infantry Brigade was busy clearing out the remaining Germans in Cuverville and Démouville to the north. After inflicting the damage, Becker skillfully withdrew his guns back to the south where more batteries of StuGs and 88 dual purpose Flak/Pak stood ready to engage the enemy.

On July 18th, Major Hans von Luck, just back from a well earned leave to Paris and recently recommended for the Knight’s Cross, pulled his car into Cagny. The village stood just south east of Le Mesnil-Frémentel and smack-dab in the middle of the British assault. The RAF had plastered the village with 650 tons of bombs in ten minutes, flattening eastern Cagny to the ground and causing confusion and lost radio contacts among the defenders.

Dismayed, the lean and wiry Luck beheld 25 to 30 British tanks bypassing the western edge of the village. His eyes scanned north to where his 1st Battalion, 125th Regiment should have been. Instead the area was swamped with British tanks moving south. “My God,” thought von Luck, “the bombing and artillery barrage destroyed the battalion.”9

Luck drove past the still standing village church when he espied a 16th Luftwaffe Division battery, its four 88mm barrels pointed into the sky. At once von Luck informed the young battery captain of the critical situation and told him to: “Hit the enemy in the flank. In that way you’ll force the advance to a halt.” The captain calmly retorted: “ Major, my concern is enemy planes, fighting tanks is your job-I’m Luftwaffe.” Von Luck pulled out his pistol and pointed it at him: “Either you’re a dead man or you can earn yourself a medal.”10

“I bow to your force,”11 exclaimed the Captain. What must I do?”Hidden in an apple orchard, the 88s lowered their muzzles at the British tanks. Salvos of 88s zoomed as Luck phrased it, “through a corn field like torpedoes.”12 Joining the Flak ambush were the last Pak 88 and Mark IV that remained at Cagny. Sixteen Shermans from the 2nd Fife and Forfar were blasted to bits.

The German gunners were trained to single out ‘command’ or other special duty tanks. It is possible that it was the Cagny 88s or Becker’s earlier ambush knocked out the 29th Brigade’s air support signal tank. It contained an airman who could call up fighter-bombers. This was a real loss to the British.

Silvertop’s 3rd RTR and its supporting motorized rifle company managed to reach the vicinity of the Cormelles factory area to the west some time after 1000. On the horizon to the north, flames and clouds of smoke spiraled up from Caen. Up to 3000 Frenchmen perished in the Allied bombing.

The regiment turned south crossing the Caen-Paris road and struck for their objectives of Bras and Hubert Folie. To their left, the 2nd Fife and Forfar pushed past Four and Soliers toward the eastern leg of the Bourguébus ridge, between Bourguébus village and la Hogue.

The two tank regiments charged up the open slope. When they were within a kilometer of the walled brick-and-stone Norman villages that dotted the Bourguébus ridge, scores of dug-in and camouflaged 88s flashed into action. The Tigers of Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Michael Wittmann’s 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion, likely joined the 88 Flak and Pak in the shoot out. Wittmann, arguably the greatest tank ace of all time, had only been promoted to battalion commander a mere eight days ago.

Major Close watched two tanks on his left get knocked out before his own rocked to the impact of an armor piercing round. “Bail out, sir!” shouted his crew. Fortunately the hit had only severed a track so that they all made it out. Close ran over to the next tank, got inside and resumed command of A Squadron. Despite his bravery, the situation turned hopeless. “Within seconds, 15 of our tanks were stationary and on fire,” he remembered. “All attempts to turn aside to left or right failed. By late afternoon we had only a few tanks left that were still in tact. The other company fared no better. We had to break off the advance and withdraw.”13

The grinding steel tracks of Standartenführer (Lt. Col) Joachim Peiper’s dreaded 1st SS Panzer Regiment’s Panthers and StuGs reverberated from the ridge. They pulled into position to greet the 2nd Fife and Forfar. Peiper’s armor was part of Dietrich’s crack unit, which General Eberbach had ordered over to the LXXXVI Corps sector to stop the imminent threat of the British armor. The open ground was perfect country for the Panther’s long-range, high velocity 75mmguns. Within a few minutes the LAH StuGs and Panthers shot up 29 Shermans, killing their commanding officers.

While the 3 rd RTR and the 2nd Fife and Forfar were being decimated, the 23rd Hussars, held in reserve around Grentheville, were temporarily ordered not to advance past Soliers. Behind them the tanks of the Guards Armored Division’s 5th Armored Brigade entered the battle. Its 1st Armored Coldstream Guards and 2nd Armored Irish Guards regiments bypassed Cagny via a detour through le Mesnil-Frémentel on their way to Vimont. But by doing so, they blocked the forward elements of the 7th Armored Division coming up from behind. Simultaneously, the 3rd Guards’ tank regiment, the 2nd Armored Grenadier Guards, engaged the Cagny 88s. Within seconds the anti-tank fire from Cagny took a toll of another 20 tanks.

To the rescue of the beleaguered Cagny Flak came nine Mark IVs and ten Tigers from the Emviélle area. Although they could drive and shoot, all of the ‘working’ Tigers of the 503rd were in rough shape and their sights were still out of alignment. Worse still, the Luftwaffe 88’s mistook them for Shermans and knocked out two Tigers. The counterattack floundered, and the Tigers and Mark IV’s drew back to Le Poirier and Frénouville.

At 1600 the troublesome 88s were finally subdued. Faced with the arrival of the Guards Division’s 32nd Infantry Brigade, the Luftwaffe crews blew up their 88s and withdrew. Wireless Guards operator G.H. Marsen describes the scene: “I could see Caen just to my right, the whole area was on fire, the earth shuddering from the bombing and shelling. I saw at least 40 Sherman tanks blazing…Our captives were mere boys, running toward our lines with hands on their heads…But they still retaliated with shellfire and most of all the dreaded ‘Moaning Mines’, the electrically propelled mortar; to be caught in their fire was certain disaster.”14 Even so, German resistance lingered on at Cagny until 2000.

Meanwhile, around 1430 the 23rd Hussars reached the smoldering tank husks of the 2nd Fife and Forfars near Soliers and Four. On the ridge, the German division commander, SS-Brigadeführer (Brig. Gen) “Teddy” Wisch, joined the LAH Panzers. They combined with Becker’s assault guns in Soliers and the Panzers in Le Poirier and Frénouville, to engulf the Hussars in a cauldron of fire.

In the words of the Story of the 23rd Hussars: “With no time for retaliation, no time to do anything but take one quick glance at the situation, almost in one minute, all its tanks were hit, blazing and exploding. Everywhere wounded or burning figures ran or struggled painfully for cover, while a remorseless rain of armor-piercing shot riddled the already helpless Shermans.”15 C Squadron lost every one of its tanks.

The 1st Coldstream Guards captured Le Poirier at 1630. Two and half-hours later, Panzer fire from Frénouville stopped an advance by the 2nd Irish Guards on Vimont. On the way there, Lieutenant John Gorman of the Irish Guards drove his tank headlong into a Tiger II plowing through a hedge. With the order “Traverse left-on-fire!”16the Sherman’s 75mm shell hit the front of the Tiger but bounced off into the air. When ordered to fire again the gunner replied “Gun jammed sir.”17 With horror the lieutenant watched the Tiger’s gun slowly turn toward him. Risking it all, the Irish troopers rammed their tank into the Tiger before it had a chance to fire. On impact, both crews bailed out, and with heavy shelling going on, both jumped for cover into the same slit trench. The lieutenant, however, crawled back to a nearby Sherman Firefly, loaded its 17-pounder gun and “brewed up the Tiger” at point-blank range. He then collected his own and the Tiger’s crew!

Heavy fighting continued at the western flank of the battle. At Bras the LAH StuGs met Pip Robert’s last reserves, his Cromwells of his 2nd Northamptonshire Yeomanry (NY) Reconnaissance Regiment. Knight’s Cross holder SS-Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Karl Rettlinger’s remembered his StuG attack: “ …2nd Company moved around Bras from the east…the 1st Company moved around from the north. The pincers caught the enemy tanks…two of their tanks burst into flames immediately and some took direct hits. Panic overtook the enemy….We lost not a Panzer. By then it was 1900hrs.”18 Sixteen Cromwells were destroyed. Together with the 33 tanks lost by the 23rd Hussars, the 45 from the 3rd RTR and the 47 from the 2nd Fife and Forfars, the 11th Armored Division lost 141 tanks. The Guards division lost another 60. Churned tank carcasses dotted the whole plain north of the Bourguébus ridge. Greasy black smoke billowed up into the air.

Hans von Luck blamed the poor British performance on lack of infantry support to take out German antitank pockets. Standartenführer (Colonel) Kurt Meyer of the Hitlerjugend asked: “Where is the spirit of the Light Brigade at Balaclava…? The enemy drag themselves across the ground like turtles….”19 In fact, slowed down by traffic congestion, by the fighting ahead of it and by roaming Tigers, the 7th Armored Division did not even manage to join the battle.38

At the end of the day, British tanks and infantry were entrenched from Le Mesnil-Frémentel-Cagny to Frénouville-Emieville. But the British advance had crawled to a standstill, and the villages on the crest of the Bourguébus ridge remained firmly in German hands. At least the British could console themselves in that human casualties were light. The VIII Corps lost 521 men, with only 81 killed in the tank regiments. Casualties among the 11th Armored’s infantry battalions were only 20, mainly because overly cautious movement and poor coordination kept the infantry from supporting their tank regiments at vital times.

On the western flank of the British Armor, the Canadian I Corps seized the Caen suburbs and factories from the 272nd Infantry Division and 16th Luftwaffe elements after a stiff fight that claimed 200 Canadian casualties. On the eastern flank, the British I Corps inflicted 651 German casualties and knocked out 18 tanks, mostly as a result of the bombardment, and drove the Germans out of Touffreville and Sannerville.

All this was less than clear at the various British headquarters, where complete confusion reigned. Army commander Dempsey even turned down an offer from RAF’s Tactical Air Force for a bombing run of Bourguébus ridge because he thought it unnecessary. Montgomery himself seemed to be on another planet. While his armor bled to death on the Bourguébus, he ecstatically sent a message to the chief of Imperial General Staff, “Complete success…bombing decisive…spectacle terrific…difficult to see what enemy can do…few tanks met so far.”20 That night at 2100, BBC news blurted out the words “Second Army attacked and broke through…General Montgomery is well satisfied.”21 Everyone thought Montgomery had achieved a second Alamein.

The Germans dreaded an infantry night attack, but none came. Instead the British consolidated their position and funneled in a number of replacement tanks for their mauled regiments. That same night it was the turn of the Luftwaffe to carry out a successful 50-plane raid against the British bridgehead. The Guards and 11th Armored Division’s administrative personnel and replacement tank crews sustained heavy casualties during the raid.

With the British poised for another assault, elements from Kurt Meyer’s 12th SS Hitlerjugend Panzer Division trickled in at 0530 on July 19. At 34 years of age, the ruthless Kurt “Panzer” Meyer was the youngest German division commander. General Feuchtinger of the 21st PzDiv rightly called Meyer the “soul of the fanatical resistance. that stopped the enemy from capturing Caen.”22 By midday, a Hitlerjugend Kampfgruppe took over the majority of 21st Panzer’s western positions as Luck’s Kampfgruppe pulled out for a rest. With Hitlerjugend holding the eastern Bourguébus ridges and the area east to the woods, and the LAH on the western ridges, the panzer divisions of the I SS Corps fought shoulder to shoulder for the first time.

At first light 3rd RTR again drove up the slope towards Bras and Hubert-Folie. Major Close related that “as we reached the line of tanks burned out the day before, we again encountered heavy fire, intensified by more tanks on the ridge.”23 No sooner had Close hopped out of his tank to help some wounded crews than a shell smashed into his own tank’s turret, instantly killing the gunner and operator. “Once again I had to turn out a tank commander and take command from his tank,”24 remembered Close.

At 0700 a company of the LAH’s 2nd SS-PzGr Regiment attacked from the village of Four and recaptured Le Poirier. To the east, a Hitlerjugend grenadier battalion with armored half-tracks repulsed weak attacks by the 32nd Guards Infantry Brigade at Emiéville.

The 2 NY went for Bras but got lost and exposed their flanks to the German guns in the village of Ifs. “Half their tanks were brewed up or knocked out”25 Close remembered. The situation changed with the arrival of British field guns by the afternoon. After they pounded the village, the 3rd RTR with grenadiers joined the assault under the cover of a smoke screen. One of the two LAH StuGs defending the village was knocked out. An SS Grenadier relates: “The tanks rolled up. Two, five, eight, ten, we stopped counting. They approached our foxholes carefully. Dread and fear paralyzed us. We knew they would pulverize us. Those of us who survived were taken prisoner.”26 The LAH grenadiers abandoned Bras at 1900, leaving many of their dead behind. By that time the victorious 3rd RTR was reduced to a pitiful nine tanks from an original 63.

While British Grenadiers were still busy mopping up in Bras, the 2 NY’s Cromwells drove on to Hubert-Folie at 1810. A hail of high-pitched machine gun fire erupted from LAH Grenadiers and StuGs in the village, supported by Peiper’s hull-down panzers farther up on the ridge, decimating the 2nd NY. At 2000 it was the 2nd Fife and Forfar’s turn to storm Hubert-Folie. To their surprise they took the village without opposition, the LAH grenadiers having pulled back up the ridge to join Peiper’s panzers at Verriéres.

An hour earlier, the 32nd Guards Infantry went for Le Poirier. The village again changed hands. But when the 32nd pushed on to Frénouville the Hitlerjugend grenadiers backed by Jagdpanzers brought them to a halt.

At Four and Soliers, the LAH’s 2nd SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment carried out a similar fight-and-withdraw tactic, at first delaying the advance of the 7th Armored Division’s 22nd Brigade’s, then pulling back to the Bourguébus-la Hogue ridge. The 5 RTR attempted to sweep around Bourguébus village but their attack again withered in the face of Peiper’s 1st Panzer Regiment. The British tankers drew back to Four and Soliers, leaving behind eight smoldering Shermans.

With nightfall of the second day of Goodwood, the British-Canadian forces stood poised in front of their prime objective, the Bourguébus ridge, which still remained in German possession. The defensive victory was especially hard on LAH’s 1st StuG battalion: reduced to only three operational vehicles left from an original 20.

The next day, July20th, saw the Guards Armored Division thrust towards the southeast, taking Frénouville and Emieville. The villages, hotly contested earlier, were abandoned by the Hitlerjugend to shorten their frontal sector. However, the youths of the 12th SS repulsed the Guards at Vimont.

In the British center, the 7th Armored Divison finally secured the likewise abandoned Bourguébus village. But its 4th County of London Yeomandry Armored Regiment and a company of the 1st Battalion Rifle Brigade were prevented from advancing further up the gentle slope toward Verriéres by the fire of Dietrich’s panzers and the Tigers of Wittmann’s 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion.

Dempsey decided that his armored regiments were too battered to continue and ordered the tanks to pull back. Eighth Corps would hold its current positions with infantry. It was now time for the Canadians to show their mettle and make a try for Verriéres.

Around 1500, supported by Canadian and British artillery fire and Hawker Typhoons, the Canadian 6th Infantry Brigade met the SS and a newly arrived Kampfgruppe of the 2nd (Austrian) Pz Div in a climatic final. In a reverse of earlier British armored attacks, which lacked infantry support, the Canadian infantry attacked with precious little tank support.

The Canadians began with a promising start. “The weather was hot and the roads were dusty,” recalled anti-tank gunner Gordon Amos, “We were green but we soon ripened up.”27 Supported by rocket firing Hawker Typhoons, the Camerons of Canada seized St. Andre-sur-Orne from the 272nd Infantry Division. Shortly thereafter the Germans plastered the village with artillery and mortar fire.

The South Saskatchewan Regiment struck for the Beauvoir and Torteval farms. German sniper fire hit the Canadians from wheat shocks. The Canadians replied with phosphorus grenades. “When the snipers see the odd guy come screaming out of a grain stook, his uniform covered with burning phosphorus, they start popping up all over the place with their hands up”27 related Captain Britton Smith.

When rain clouded the skies and drove off the Typhoons, Mark IV panzers of the 5th and 6th companies of the LAH’s 2nd SS Panzer Battalion, a StuG company and SS grenadiers viciously counter assaulted. MG-42’s nicknamed “Hitler’s scythe and buzz saw” cut down scores of Canadian infantrymen. Panzer shells burst up the few supporting Canadian tanks. The Canadians in the center broke and ran through the cornfields. Panthers rampaged through the wheat fields with impunity, flushing out their hidden prey. Two companies of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal were all but annihilated. In its first real action, the South Saskatchewans alone took 208 casualties, including their commander.

The Essex Scottish Regiment was up next. Lance-Bombardier Munro remembered: “its our men against tanks – the best tanks in the war…at the same time we’re facing heavy mortar and artillery fire.”29 A retreating South Saskatchewan yelled, “It’s bloody suicide up there!”30

Despite their bloody casualties, the tough Canadians gritted their teeth and kept fighting. The German versus Canadian duel continued throughout the night. Thunder boomed in the sky and the rain poured in buckets over the war torn slopes. The ground turned into a quagmire. Unrelenting fire from their field guns enabled the Fusiliers Mont Royal to hold onto Troteval farm into the next morning.

Artillery Captain Britton Smith remembers: “He’s [a tiger] so bloody close-only two hundred yards away–that each time he fires, the muzzle blast bang our ears together and flattens the grain all around us as the shot screeches overhead and a shower of sparks goes up from one of our tanks up on the hill…I put a battery of mediums on him and hammer him for about half an hour. I may not have knocked him out, but I’ll bet I loosened up the bowels of the crew.”31 The artillery fire copes with the enemy infantry but “when they begin coming with tanks, we realize the jig is up.”32

Renewed attacks by the LAH in the morning of the 21st brought the Essex Scottish casualties up to 301. The regiment was only able to withdraw due to a timely appearance by the Canadian Black Watch alongside tanks of the 1st Hussars and Sherbrooke Fusiliers.

Goodwood had reached its end; the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS had shredded the British and Canadians to pieces. Skillfull fighting withdrawals combined with aggressive and well-coordinated counterattacks within a deep defensive belt demonstrated the German genius for a fluid defense. Sepp Dietrich also praised the mechanics of the nearby German tank repair shops. The mechanics, who made extensive repairs within a few short hours, had been vital for keeping his armor in battle. Dietrich personally awarded them the Iron Cross Second Class.

Aided by poor weather, that limited Allied air support, and poor British coordination and intelligence, Goodwood became perhaps the greatest German defensive victory of the Normandy campaign. The British suffered 3,474 casualties among VIII and I corps, the Canadians another 1,965. Two hundred and fifty three tanks were destroyed, although a fair number of them were later repaired. On the other hand the Germans likewise salvaged enough Shermans to equip an entire company of the 21st Panzer Division. The heavy British and Canadian sacrifices only extended the Allied bridgehead by only nine kilometers and failed to secure the vital crest of the Bourguébus ridge. Though the British-Canadians held most of the northern slope, only one of the five main tactical objectives, the village of Hubert-Folie, had been secured.

Goodwood also failed to “write down the German armor,”33 as Montgomery had phrased it. The Germans lost only 75 tanks in the battle. And, significantly, more than 40 of those were lost to Allied bombing. German personnel losses were relatively light as well, though the continuing attrition was clearly wearing down the panzer divisions.

Incredibly, Montgomery calmly claimed that Goodwood achieved everything he hoped for. The validity of his position after Goodwood when compared to his prebattle expectations has been much debated. This was because Dempsey’s original operational order had also listed Falaise as one of the objectives. On July 15th, however, Montgomery changed Falaise to a target for reconnaissance units only, but then failed to notify Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) of the change. The likely reason was that Montgomery doubted that Goodwood would achieve a decisive breakthrough, but publicly he supported this notion to gain the required air support.

What the British and Canadian troops expected became clear to von Luck. Canadian prisoners told him that Monty had called out: “To Falaise, boys, we’re going to march on Paris.”34 SHAEF certainly expected as much. Furious at Monty’s failure, Eisenhower commented that the Allies could hardly expect to advance through France at the rate of 1,000 tons of bombs per mile! All the senior Air commanders were angry, as they had been eager to secure airfields for their short-range fighters south of Caen. Even Churchill was disappointed with Monty. With many calling for Mongomery to be fired, Goodwood was another nail in the coffin that buried his chance of remaining overall land force commander.

In Montgomery’s defense, though, Goodwood managed to draw the bulk of the panzer divisions away from the American western flank. On July 25th the American breakout of “Cobra”, delayed by the bad weather, finally got underway to coincide with “Spring” another British-Canadian offensive with virtually the same goals as “Goodwood.” By that time there were seven Panzer divisions facing the British-Canadians as opposed to the two Panzer divisions and one Panzergrenadier division that bolstered the German infantry divisions facing the Americans. Nevertheless, the major contribution of Goodwood was not so much the diversion of German armor but rather the diversion of the deteriorating German supplies to the British sector. When Cobra broke loose in the St. Lô sector, the Germans not only faced a better-planned and-executed operation but also lacked the supplies to sustain an effective defense.

Notes

- Hans von Luck, Panzer Commander (New York: Dell Publishing, 1991) p. 199.

- Carlo d’Este, Decision in Normandy (London: Collins, 1983) p. 370, 371.

- J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World (New York: Granada, 1970) p. 558.

- David Mason, Breakout: drive to the Seine (London: Macdonald & Co. 1968) p. 9.

- Michael Reynolds, Steel Inferno. 1st SS Panzer Corps in Normandy (New York: Dell Publishing, 1998) p. 207, 208.

- Ibid, p. 209.

- Ibid, p. 215.

- Hans von Luck, Panzer Commander (New York: Dell Publishing, 1991) p. 196.

- Ibid, p. 193

- Ibid, p. 193.

- Ibid, p. 194

- Ibid, p. 197

- Ibid, p. 197

- Alexander McKee, Caen Anvil of Victory (London: Souvenier Press, 1964) p. 272, 273.

- Ibid, p. 272.

- Ibid. p. 274.

- Ibid. p. 274.

- Michael Reynolds, Steel Inferno. 1st SS Panzer Corps in Normand, p. 220.

- Ibid p. 222.

- Carlo d’Este, Decision in Normandy, p. 381

- Alexander McKee, Caen, Anvil of Victor, p. 278

- James Lucas, Hitler’s Commanders (Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2014) p. 128.

- Alexander McKee, Caen, Anvil of Victor, p. 278.

- Ibid, p. 279.

- Ibid, p. 279.

- Michael Reynolds, Steel Inferno. 1st SS Panzer Corps in Normand, p. 226.

- Alexander McKee, Caen, Anvil of Victor, p. 286.

- George C. Blackburn, The Guns of Normandy (Toronto: McClelland & Steward, 1995) p. 184, 185

- Ibid, p. 189.

- Ibid, p. 189.

- Ibid, p. 190, 191

- Ibid, p. 192

- Russell A. Hart, A Clash of Arms (London: Lynne Rienner, 2001) p. 314, Michael Reynolds, Steel Inferno. 1st SS Panzer Corps in Normand, p. 209, 231.

- Hans von Luck, Panzer Commander (New York: Dell Publishing, 1991) p. 201.

Sources

Bercuson David J. Maple Leaf against the Axis. Toronto: Stoddard. 1995, Blackburn George C. The Guns of Normandy. Toronto: McClelland & Steward. 1995, Blumenson Martin. Liberation. Virginia. Time Life Books. 1978, d’Este Carlo. Decision in Normandy. London: Collins. 1983, Donnelly Tom and Naylor Sean. Clash of Chariots. New York: Berkley Books. 1996, Fuller J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World. New York: Granada. 1970, Hart Russel A. Clash of Arms. London: Lynne Rienner. 2001, Luck, Hans von. Panzer Commander. New York: Dell Publishing. 1991, Mason David. Breakout: drive to the Seine. London: Macdonald & Co. 1968, McKee Alexander. Caen Anvil of Victory. London: Souvenier Press. 1964, Reynolds Michael. Steel Inferno. 1st SS Panzer Corps in Normandy. New York: Dell Publishing. 1998.

Net Sources

http://www.onwar.com/maps/wwii/normandy/1goodwood44.htm, http://www.generals.dk/, http://www.panzerace.net/main/normandy.asp, http://home.att.net/~SSPzHJ/KurtMeyer.html, http://web.archive.org/web/20010405162157/valourandhorror.com/DB/CHRON/July_18.